Why does a historical fiction author choose a particular time to write about? And what happens when your characters insist on staying in your head when a series ends? SG MacLean, whose The Winter List is just out in paperback, writes about how she was drawn back into the world of Damian Seeker one last time.

One of the most frequent questions I am asked as a historical novelist is why I chose a particular period to write in. In 10 of my 11 novels to date, that period has been the 17th century. Those who, like me, have fallen under the spell of that century, tend to be bemused as to why anyone is interested in any other.

Two friends, both senior academic historians and fellow 17th-century devotees, were actively troubled when they learned I was slipping off into the 18th (for my 10th novel, The Bookseller of Inverness), and urged me not to hang around there too long.

So what is it about the 17th century? For me, primarily, it is that that is the century when we really begin to hear the voice of the man and woman in the street, and also of the middling sort – doctors, teachers, clerics, lawyers – often speaking in the vernacular.

It is these characters, often lost to the anonymity of history, as opposed to the kings, queens and aristocrats who largely leave me cold, who have always most interested me. It is in the 17th century that in the British Isles we see these people seize the historical moment. They lay forth their ideas in newspapers, they take up arms, for a time, they take control.

As someone engrossed in Scottish history for most of my adult life, my interest in English history was, at best, tangential, until the seed of for the Damian Seeker novels planted itself in my head and I began to delve into the world of the Cromwellian Protectorate. Pace, Tudorists, but the Cromwellian period is surely the most incredible, astonishing and utterly intriguing in English History.

For five novels in the Seeker series, I immersed myself in the Protectorate, always knowing that my main character, an agent-handler in Cromwell’s intelligence service, would not remain in England after its fall. He would have no place in Restoration England and had the exit I had always planned to give him. And yet…

In the course of my reading for the Seeker novels, there were two books in particular which focused on aspects of the Restoration that told a quite astonishing and, to me, new story.

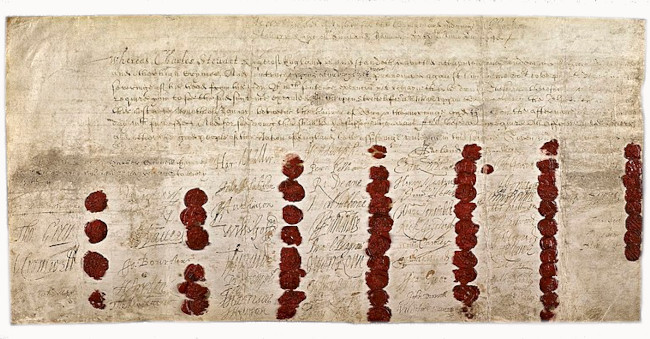

Don Jordan and Michael Walsh’s The King’s Revenge and Charles Spencer’s Killers of the King both deal with the hunt for the regicides of Charles I that followed the Restoration of the Stuarts under his son, Charles II.

The hunt for the regicides is not one story, but a series of stories of revenge, brutality, courage, intrigue, betrayal, loyalty, endurance and guile encompassing the British Isles, Europe and North America. Men who in the Cromwellian era had risen from obscure or middling origins to live for a short while in palaces and to rule nations, were hunted for their lives. There was a novel, a whole raft of novels surely (we will come to Robert Harris presently), in there somewhere.

I however, like the Protectorate, was finished. I knew where Seeker was and how he was getting on, even if my readers did not, and I was content. Other ideas were pulling at me.

Specifically, I wanted to come closer to home (the Scottish Highlands) and write about my own history and culture, and I eventually embarked on that excursion into the 18th century with The Bookseller of Inverness.

And yet … Over time, I became increasingly aware of the voices of the 17th-century man and woman in the street murmuring in my head. One in particular would not be quiet. It was Lawrence Ingolby, the cocky young Yorkshire lawyer I had created in the third Seeker book, Destroying Angel, and had liked so much that I took him from that book to put him into the rest.

Lawrence, while my favourite, was only the most prominent amongst a range of characters – spies, turncoats, landladies and coffee house keepers — who had accompanied Seeker throughout his adventures and of whom I had become very fond. “What about us?” demanded Lawrence. “What happens to us when the Stuarts come back?”

I suppose I had spent so long with them all that I missed them. I needed to finish off their story, let readers know what became of Lady Anne Winter, Sir Thomas Faithly, Manon, Lawrence, and, of course, Seeker’s dog.

The real historical characters of Andrew Marvell and Samuel Pepys, each of whom had cheered my days and who had very adeptly pirouetted with the change of regime which restored the Stuarts were also jostling in my head, demanding their walk-on roles.

With Seeker off stage, I wanted to show them all in the new reality they had to deal with. I didn’t want to get bogged down in the fracturing politics and military disintegration of the dying days of the Protectorate, I would show them in the Restoration.

My favourite setting of the Seeker novels had been York and it was to York I decided to return and where I would cast my characters loose as players in the story of the hunt for the regicides.

The day after agreeing all this with my editor, I sat down to start making notes, writing across the top of the blank page, Act of Oblivion. At coffee time, I scrolled through the Bookseller daily bulletin to read the dreadful words (to the effect of): Robert Harris, new book coming out next year: Act of Oblivion, the hunt for the regicides!

Within seconds, I was firing off a despairing email to my editor. “Don’t worry,” she soothed. “You will write a different book.” And so I did, and whether or not I had ever intended to call it Act of Oblivion I no longer know. It is called, instead, The Winter List, and I hope it answers all the questions about what did happen to everyone from the Seeker books, maybe also to the big man himself.

The Winter List by SG MacLean is published in paperback on 9 May, 2024.

SG MacLean has been shortlisted four times for the CWA Historical Dagger and has won it twice, for The Seeker in 2015 and for Destroying Angel in 2019. The Winter List was longlisted for this year’s Historical Dagger Award.

You can find her on Instagram @shonamacleanauthor

You may also enjoy Historia’s interview with her, where we talk more about The Winter List, historical research (including in a flood-swept York) and her plans for her next novel.

Read Alis Hawkins’s review of The Bookseller of Inverness, her previous novel, which is set in the Highlands after the Battle of Culloden.

There’s more background information in Killing a king: the execution of Charles I by Leanda de Lisle.

Images:

- Some of the regicides (L–R Cornelius Holland, Thomas Scott, John Bradshaw, Oliver Cromwell, Thomas Harrison) with the Devil, detail from Olever Crumwells Cabinet Councell Discoverd, 1649, from A Vindication of the Royal Martyr, King Charles I by Samuel Butler: British Museum (public domain)

- John Thurloe, head of intelligence during the Protectorate, by Jacobus Houbraken, 1738, after Samuel Cooper: Yale Center for British Art (public domain)

- Death warrant of Charles I, 29 January, 1648/9: Parliamentary Archives, HL/PO/JO/10/1/297A via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Detail from Charles II dancing at a Ball at Court by Hieronymous Janssens, 1660: Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024

- Goodramgate, York, in the snow: by SG MacLean