17 November is St Hilda’s feast day. Who better to write about the 7th-century Abbess of Whitby’s world than Nicola Griffith, whose novel Menewood, the second in her retelling of Hilda’s (or Hild’s) life, has just been published in paperback? Here she looks at the battle which opens her book: Hatfield, in 632.

Menewood is set in early 7th-century Britain. It is a book about war — bitter war, winter war — book-ended by two famous battles. These battles are attested by a variety of chroniclers, some of whom are regarded as at least occasionally reliable (Bede, Adomnán), and some, well, not so much. As written, one battle makes complete sense; the other, though, is a problem: it relies on divine intervention.

Battles, of course, are just a small part of the massive and wide-ranging project that is war. To succeed, a leader — in the case of Menewood, Hild, also known as St Hilda of Whitby — must harden their defences; negotiate alliances; survive defeat; gather and grieve with other survivors; learn from their losses; and rebuild.

While rebuilding, they must form a new set of alliances, create new power structures, and then recruit, train, plan, supply, and lead those who will join with them to successfully prosecute a war, to survive that and minimise the horror, and then to move through and past that violence to a hope for a better future. If there was anyone in early 7th-century Britain who could do that, it was Hild.

Hild was real. Almost everything we know of her comes from a single document, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (HE), written by the Venerable Bede, a Christian monk, about fifty years after her death.

If we are to believe Bede — who was a careful historian but writing with an agenda and within the cultural constraints of his time — Hild was born circa 614, probably in the north of what is now England, and died in her bed 66 years later as the Abbess of a large and important religious foundation in what is now Whitby.

We know her mother was Breguswith and that her father, Hereric, was poisoned in West Yorkshire (Elmet) when Hild was three. When she was 13 she was baptised in York (Eoferwic) alongside her (great-) uncle, Edwin Yffing, king of Northumbria, and was recruited into the church when she was 33.

Of the rest of the first half of her life — including the years covered in Menewood — we know only that she was “living in most noble conversation in secular habit.” (HE, IV, 22; all quotes are my own sometimes rather literal translations from Latin and Old English.) We don’t know where, or doing what, or with whom.

However, during the second half of her life, as abbess, we know “her wisdom was so great that not only ordinary people, but even kings and princes sometimes asked for and” — the part that made me sit up and pay attention — “took her advice.” In other words, the kings of seventh-century Britain, who took and held power by violence (for several generations before and after Hild’s birth, without exception every king of Deira, Bernicia, or a united Northumbria died in battle), regarded Hild as knowledgeable enough in their arena to be worth listening to.

We know she was also an effective facilitator and administrator — she hosted the history-changing Synod at Whitby — a teacher (she trained five bishops), a forward thinker (she saw the value in using vernacular literature to convey ideas — Cædmon composed under her aegis), and made an indelible impression on others (she is still venerated as a patron saint of learning and education 1,350 years after her death).

Given that people rarely have total personality changes mid-life, we can assume Hild had these qualities before she joined the church — and on that assumption rests the events of Menewood.

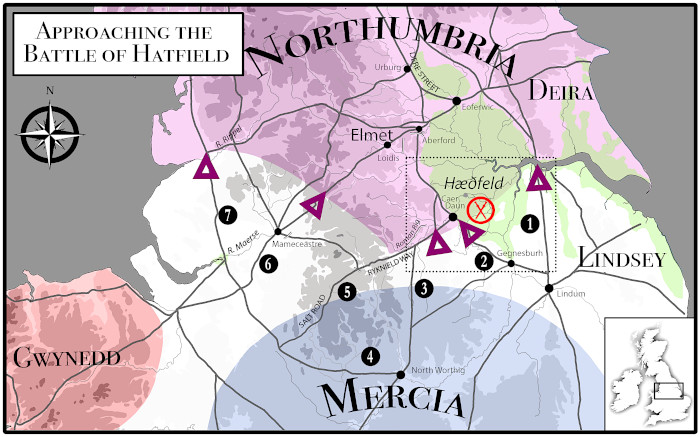

The book’s first main battle, the Battle of Hatfield, is dated by Bede to October 12, 632. At that time, troop movement was very often via the Roman road system — which the Romans had designed primarily for that purpose. Even 200 years after the insular tax-and-maintenance structure of Empire collapsed, these roads were the best and often only practical military routes.

You have only to consider five of the early-medieval North’s most significant battles (see the map, right) to see that one route in particular had become a warstreet.

According to Bede, the army of Edwin of Northumbria was defeated by the combined forces of Penda of Mercia and Cadwallon of Gwynedd at a place Bede names Hæðfeld, usually assumed to be what is now Hatfield Chase near Doncaster (Caer Daun). Edwin and Osfrith his son are dismembered and their heads and limbs impaled on stakes.

If we assume that the armies of Mercia and Gwynedd — separately or collectively — would march from their respective territories to the most convenient entry point to Northumbrian territory and that Edwin would engage them there, then Bede’s account seems straightforward.

From Cadwallon’s Gwynedd and Penda’s Mercia, there are few practical routes into Northumbria. On paper, the westernmost route (7) running from Chester across the Mersey (Maerse) and then across the Ribble (Rippel) looks reasonable, at least for Cadwallon. But by the early 7th century, after the marine incursion, rising sea levels, and the loss of imperial maintenance, the Maerse would have been essentially impassable.

Even if, somehow, that was managed, then the Rippel crossed, they would be on the wrong side of the Pennines — the richest parts of Northumbria, that is, Deira and Bernicia, are in the east — with winter coming.

It’s a similar story with the next route (6) following the Manchester (Mameceastre) to Leeds (Loidis) road over the Pennines. Cadwallon would be better advised to take what I think of as the Salt Road (5) through the Peak District. It’s high but likely to be in good repair to facilitate trade (salt, iron, lead) with the Pecsætne.

That would get the troops to Ryknield Way which skirts the southern boundary of Elmet (part of Northumbria since Edwin’s accession). A massive defensive earthwork, the ‘Roman’ Rig, would keep the army on the road and heading northeast towards Doncaster (Caer Daun).

It’s also possible Cadwallon took a longer but much easier route (4): swinging south of the Peaks to Mercia, meeting Penda’s men in North Worthig (Derby), and the combined force then moving directly north (3) to Ryknield Way.

On Ryknield Way there are two choices: continue to Caer Daun and, from there, north along probably the most used military road in Britain, the alternate Ermine St (alt-E) that, after Eoferwic, becomes Dere St and continues its march north. Or take the branch that cuts the corner and meets alt-E north of Caer Daun.

Penda could have taken (3) to Ryknield Way and be faced with the same choice. Alternatively, he could have moved along (2), which would meet alt-E at Gainsborough (Gegnesburh), and then march for Caer Daun. We can dismiss Ermine St itself (1), running from Lincoln (Lindum), across the Humber to Brough. The Humber is too wide to bridge and the efficient Roman ferry system had long since vanished.

It was almost inevitable, therefore, that Penda and Cadwallon would meet Edwin’s army where the warstreet crosses from disputed territory at or near Caer Daun. If Penda and Cadwallon were smart and planned a pincer movement, they could then drive Edwin into the mire to be slaughtered. And this is how I imagined it happening.

After the Northumbrians are defeated and killed, Penda and Cadwallon march north. At some point, Penda abandons Northumbria to the tender mercies of Cawallon and returns to Mercia. What follows is over a year of horror and chaos.

The thrones of Deira and Bernicia are variously claimed by Osric Yffing (Edwin’s cousin) and Eanfrid Iding (older half-brother of Oswald, living in exile among the Picts). Both are promptly slaughtered by Cadwallon, who, Bede tells us, was “so barbarous in heart and manners, that he spared not even the female sex or the harmless little ones, but put them to death by the tortures of the wild beasts of all nations.” (HE, II, 20).

He apparently Harrowed the North so savagely that this time was “unlucky and destitute of good things.” Therefore “it pleased all those who counted the times of the kings, that the memory of the perfidious kings being removed from among them, the same year should be assigned to the reign of the next king, that is, to Oswald, a man beloved of God.” (HE, III, 1)

Oswald, like the northern kings before and after him, took power on the battlefield — in his case, the Battle of Deniseburna.

Menewood by Nicola Griffith was published in paperback on 1 October, 2024. It’s the sequel to Hild.

See more about this book.

You may also like to read History, historicity, historiography and Arthurian legend, also by Nicola.

Historia features on early medieval England include:

Anglo-Saxon women with power and influence and In search of Mercia by Annie Whitehead

The royal women of 10th-century England and Adding the ‘little’ bits to enrich a story of Saxon historical fiction by MJ Porter

A life of war in Anglo-Saxon Britain by Edoardo Albert

The ways of war at the time of King Alfred by Chris Bishop

Oswald: Exile, King, Saint by Matthew Harffy

Images:

- St Hilda of Whitby, window by Kempe in St Nicholas’s Cathedral, Newcastle: Lawrence OP for Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

- Bede writing his Ecclesiastical History of the English People from Omiliae lectionum sancti evangelii Venerabilis Bedae presbiteri numero quinquaginta, 12th century: Stiftsbibliothek in Engelberg, Switzerland, codex 47, via Wikimedia (public domain)

- St Hilda of Whitby, detail from the west window of All Saints’ Cowley by Sir Ninian Comper: Lawrence OP for Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

- Greyscale map of early 7th-century Britain showing selected peoples and polities, five late-6th to mid-7th century battles, and a simplified representation of a Roman road: created and © Nicola Griffith. See a high-res version on Nicola’s website

- Greyscale map of the north of Britain showing possible routes taken by armies to the Battle of Hatfield: created and © Nicola Griffith. See a high-res version

- Cadwallon fab Cadfan of Gwynedd from Brut y Brenhinedd, 15th century: the National Library of Wales/Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru, Peniarth MS 23 (public domain)