Carolyn Kirby, award-winning author of When We Fall and The Conviction Of Cora Burns. talks to AD Bergin about her new novel, Ravenglass. A sweeping adventure with a cross-dressing main character, Kit, it’s set against a backdrop of 18th-century social and industrial revolution, the lesser-known regional slave trade, and the Jacobite rising of 1745.

AB: I thoroughly enjoyed reading Ravenglass, which both immerses the reader in a very particular time and place but deals also in universal themes of identity, love, loss and the tension between individual, family, and community. Why in particular this book, with its specific themes?

CK: Ravenglass has been long in the gestation, so that’s not a quick answer. Thirty years ago, I first read Amanda Vickery’s The Gentleman’s Daughter with its focus upon the lives gentlewomen in the 18th-century North and became struck by the sense that real women from that time were speaking directly to me.

That was long before I even thought about fiction writing, but exploring the lives of women in historical context has since become a core interest in all my books. Following on from When We Fall and Cora Burns, I was exploring a novel about Bonnie Prince Charlie and his amazing life. The two interests merged in Ravenglass.

Then I had this idea of exploring these themes through a ‘stranger comes to town’ character, able to look at things with fresh eyes, which opened me to thinking ‘why not a cross-dressing Jacobite?’ So, the character of Kit came into being.

AB: I keep recalling the words with which you have Kit conclude the book. “Before you judge me, read my words and make your own mind up about the person I have become.” Kit is a remarkable realisation of nuance and complexity in terms of gender, dress, sexuality, familial roles and wider social respect. Similarly, the transatlantic slave trade has a major impact, in differing ways, on almost every character in the novel. This is all highly contested territory, in which Ravenglass is never dogmatic, always nuanced. That feels like a deliberate approach.

CK: Yes. Kit as a character really took over and was such a pleasure to write, so I can’t underestimate the significance of that. Kit, does however, live as a ‘he’, then, when Stella, as a ‘she’. Really, what I very much wanted to reflect in Ravenglass and many of its characters is the humanity, warmth, wit, and resilience of the LGBTQ community.

The topic of the transatlantic slave trade meanwhile links to my previous interest in Nazi atrocities in When We Fall. We tend to think today, “how can they have done these things? Yet ordinary people did engage with the slave trade, for more than a hundred years.

As with the Nazis, most of those involved in these terrible crimes thought of themselves as upright, Christian, moral people. I wanted to try to understand things from the perspective of those who perpetuated the trade and so challenge the condescension of posterity, whereby we believe ‘we’ are all so much more educated and intelligent now and would not get involved.

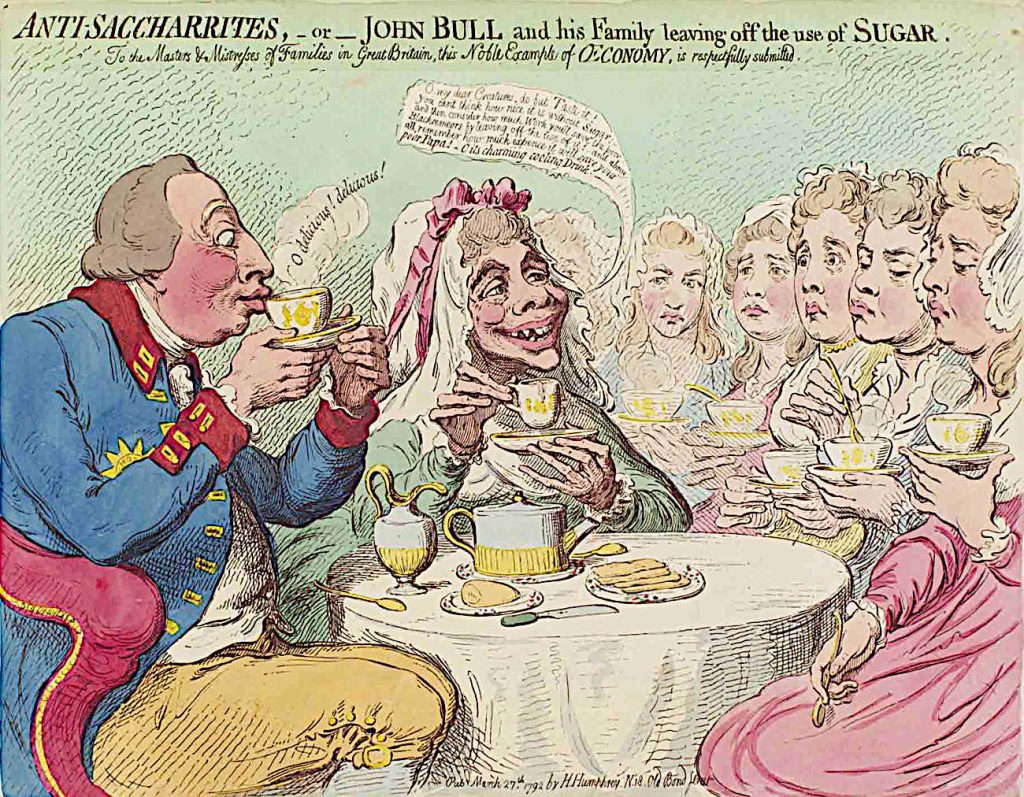

That simply fails to address how people felt and thought at the time. Think about it this way; famously, there was a major 18th-century boycott of sugar, which became a central plank of the abolition campaign in Britain. Yet we aren’t today seeing similar calls for a boycott of mobile phones because of the horrendous exploitation happening in the cobalt mines of the Democratic Republic of Congo. So yes, we need to think much harder about moral absolutes, and not just in in relation to history.

AB: That is very interesting and is precisely the perspective other recent Northodox Press historical novels explore. How important was it to find the right publisher for this story?

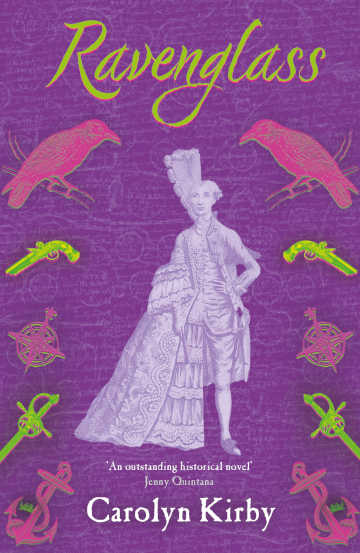

CK: I’m very grateful to Northodox for believing in Ravenglass and couldn’t imagine better publisher for this book. I heard about their acceptance when I was in Grasmere and to have a strong northern publisher was perfect, a real fit, understanding of what I was trying to do, support, and of course a lovely cover and design.

Because the whole book really is a love letter to the North. It is great to have northern stories heard, and to have found a publisher that isn’t afraid to take on such morally grey areas.

AB: Following on from that, a lot of detailed research clearly went into Ravenglass, albeit worn with beautiful lightness. Where did you start and what sources were most useful?

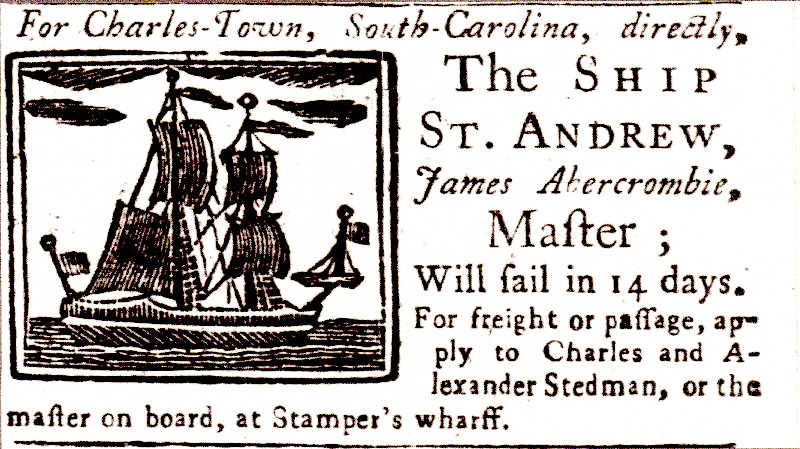

CK: I do need my books to have a solid foundation of historical fact and then weave through it a gripping fictional plot. Jacobites, a new history of the 45 by Jaqueline Riding, was fantastically helpful, as was The Forgotten Trade by Nigel Tattersfield, which details the involvement of traders from minor ports such as Whitehaven in the developing slave trade.

We also know for example, that there were four real female Jacobite prisoners held in the House of Correction in Whitehaven and that they escaped, so I thought what if Kit could have been one of them?

In fact, Ravenglass was a real pleasure to research, in particular discovering so many books and other sources about its key places, first of all the wonderful Whitehaven 1600–1800 by Silvia Collier, published by the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England and replete with maps, illustrations of houses and door fronts from the 18th-century town, which became so useful in being able to place the narrative.

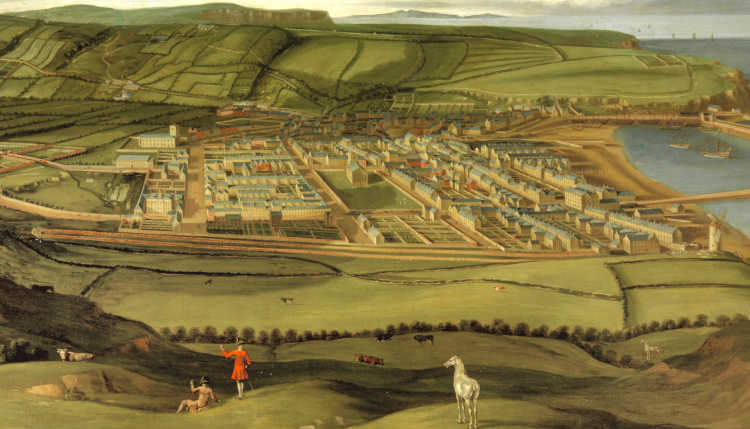

There is also the Birds-Eye-View by Matthias Read, an incredible painted view of Whitehaven in 1736, as well as a later engraving, with key, which shows in detail the location of the town’s churches, its principal buildings and thoroughfares. Together, they allowed me to root the characters and plot in a very real setting.

The material reality of the time is of significant importance to Ravenglass. Early in the research, through St. Hilda’s College, Oxford, I contacted Dr Julie Farguson, whose specialism centres on Stuart and Hanoverian material culture and also shipping. She is very interesting on the economics of trade in the period such as the details of naval prizes, but was also terrifically helpful in terms of wider material culture.

Then, there is the Museum of Scotland’s 2017 Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites exhibition, a trove of material culture, whose catalogue and online resources became invaluable alongside, among other specialist books, fashion historian John Styles’s The Dress of the People, a history of everyday fashion in the 18th century, which particularly focuses upon the shift from linen to cotton, linked, of course, to developing global trade, not least the Transatlantic slave trade which is central to my book.

What does also help is my lifelong interest in historical costume, to the point of hopefully dating any historical fashion to within five years!

AB: With its wide sweep, dashing escapades, ever-changing cast of characters and big redemption arc, Ravenglass recalled to me classic 18th-century literature such as Tom Jones or Clarissa. Was there a conscious evocation of that lineage?

CK: Very much so. It is a wonderful tradition, and in writing Ravenglass, I read or re-read so many of those novels. It can be a matter of wading through in the odd case, but an absolute romp in the case of others. Smollett’s The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker was a great discovery, for example, an epistolary travelogue which you just cannot stop reading.

AB: The very best fortune for Ravenglass. It certainly deserves tremendous success. What can we expect next?

CK: The next thing has been going for a long time. There is no title yet, but it is a detective novel set amongst the early archaeologists of Salisbury Plain, the barrow diggers. Its theme is about the power of the dead over the living, so I have been spending a lot of time in the Iron Age as well as in the early 19th century.

Ravenglass by Carolyn Kirby is published on 25 September, 2025.

Read more about this book.

Carolyn has written several pieces for Historia, including:

Fifty years of fake news; the cover-up of the Katyn Massacre

‘Paedo Hunter Turns Prey!’ The ironic fate of the father of tabloid journalism

And interviews with Clare Mulley about Krystyna Skarbek and about her book Agent Zo; with Luke Pepera; and with AD Bergin about his debut novel (see below)

She’s also reviewed The Mare by Angharad Hampshire and A Prince and A Spy by Rory Clements

The Wicked Of The Earth by AD Bergin was published on 21 November, 2024.

Read Carolyn interviewing AD Bergin about the history behind his novel, or find out more about this book. It’s set against the background of Newcastle’s 1650 witch trials, and has been longlisted for the 2025 HWA Debut Crown Award.

Its sequel, Jerusalem Staggers, will be published in Autumn 2026.

Historia features related to Carolyn’s new book include:

Five surprising facts about Charles Edward Stuart,

Remembering Culloden, and

Raising the Jacobite standard: Glenfinnan, 1745, all by Frances Owen

Damn’ Rebel Bitches: Research Then and Now by Maggie Craig, about Jacobite women

The Scot who was the Caribbean’s first serial killer by PD Lennon looks at the crimes of a sugar plantation owner in Jamaica

A respectable trade in brutality: Blood & Sugar by Laura Shepherd-Robinson

Reassessing Francis Drake: what research for my novel revealed about his role in the slave trade and Maria: the African woman who sailed with Drake on the Golden Hind by Nikki Marmery

Images:

- Birds-Eye-View of Whitehaven by Matthias Read, c1736: Wikimedia (public domain)

- Prince Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie), (circle of) Louis Tocqué, 1748: Traquair House via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Anti-Saccharrites by James Gillray, 1792: Wikimedia (public domain)

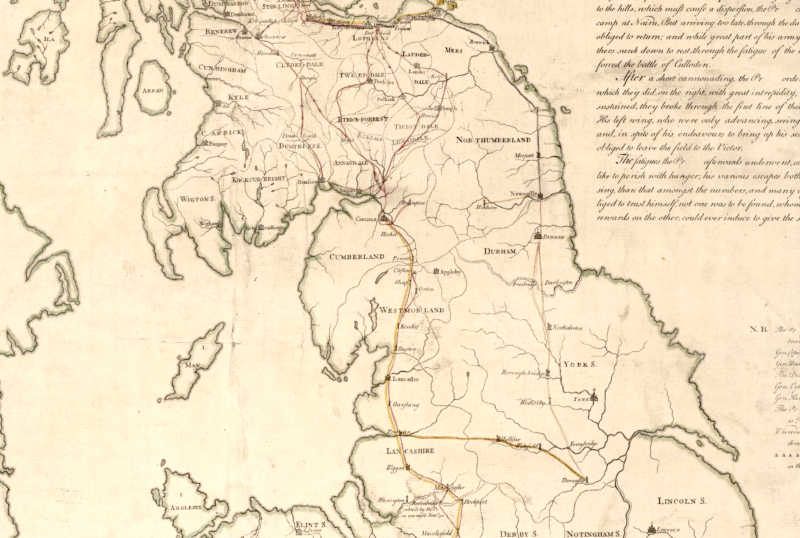

- A general map of Great Britain; wherein are delineated the military operations in that Island during the years 1745 and 1746 and even the secret routs of the Pr after the battle of Culloden until his escape to France: illustrated by an authentic abstract by John Finlayson and Alexander Baillie, 1751: Signet Library collection of maps, National Library of Scotland (CC-BY-NC-SA)

- Advertisement, The Ship St Andrew, Pennsylvania Gazette, 2 November, 1749 (made numerous voyages from Virginia to the Caribbean trading in rum, merchandise and slaves, including an 1749 voyage to Antigua to pickup slaves): Wikimedia (public domain)

- Flora Macdonald (Fionnghal nighean Raghnaill ’ic Aonghais Òig) by Richard Wilson, 1747: © National Galleries of Scotland collection. Photo, National Galleries of Scotland