When the perfect idea for a novel presents itself, but then you find that your source is (factually and morally) questionable, how do you approach it? By telling the story behind the stories, RJ Wilton suggests in his account of the challenges he faced in writing a novel set in early 20th-century Morocco.

Sultan Abd-al-Aziz of Morocco was said to have bankrupted himself collecting European bric-à-brac at the beginning of the 20th century: “Grand pianos and kitchen-ranges; automobiles and immense cases of corsets… an infinity of all that was grotesque, useless, and in bad taste.” His brother and successor/usurper, Sultan Abd-al-Hafid, had a passion for mechanical devices: “Nearly everything was broken and an Italian watchmaker was employed in trying to sort out the wheels, bells and other internal arrangements.”

And as easy as that, I knew the story I was going to write. It helped that I was lying in a hammock, on a roof-top on the Moroccan coast. The jumble of roofs around me, the seagull cries jousting with the call of the Muezzin, and in the endless market alleys such a bustling of spices and shadows and fabrics and electric-tangy tea. Just for once the question wasn’t how I could write, but how I could not write a historical novel.

“At this critical moment”, recounted long-term Morocco resident Walter Burton Harris, “came word of a belated circus at one of the coast towns. It must naturally have been a very poor circus ever to have found itself at that dreary little port, but its advent was welcomed as enthusiastically as if it had been Barnum’s entire show.”

The icing on the piece of cake; the cliché on the cliché. All of that rich and quirky historical colour, energized by a radical narrative factor. Stuff writes itself. I’d finished the first page or so before I even clambered, with my usual spectacular inelegance, out of the hammock.

Harris – who was also the source for all that good stuff about the Sultans – was himself quite a character. Officially correspondent for The Times, he was one of the first Europeans who settled in Morocco because it was more tolerant of his lifestyle choices. He enjoyed travelling the country in elaborate native disguise, and was kidnapped by a notorious bandit chief – who became a good friend.

It was at about this point that the wheels started to come off my circus wagon. The more I considered Walter Harris, the less comfortable I was. His anecdotes are entertaining, but they’re generally in the service of the greater glory of Walter Harris. Let’s just say he was a bit of a historical fiction specialist himself, and enviably readable.

But what did that mean for the rest of his stories? Where was history and where was fiction, among his filthy, violent, tricksy, ridiculous Moroccans – and in particular the absurd hobbies and enthusiasms of the Sultans?

Harris’s representation of its people was typical and influential among European writers. Their attitudes – the colourful exaggerations, the orientalism, the exoticism, the soft-touch hard-wired racism – were felt far beyond the Maghreb.

The events of 1906, when The Sultan’s Emu is set, were among the last spasms of the Scramble for Africa, the European competition for influence and territory across the continent. While Sultan Abd-al-Aziz was enjoying his circus, his representatives were on the other side of the Mediterranean failing to secure the future of their country.

At Algeciras in southern Spain, the diplomats of the European Great Powers had gathered to haggle. The conference had been prompted by an impetuous German bid for a say in Moroccan affairs. The Moroccans went into it hoping to shore up their independence. They came out of it three months later having signed over their security and economy to the French. (Even my perception of the real events is fictive: our history syllabus is among the most notorious clichés in our narrative tradition.)

By now, the wheels of my circus wagon were long gone and it had come to a dead halt in a sand dune. I didn’t want to be another Walter Harris, conjuring and manipulating some generic and comic ‘Africans’ to give a bit of appealing colour and moral context for a European tale for European readers.

The great Nigerian novelist and critic Chinua Achebe noted that for western writers, “there are no real people in the Dark Continent, only forces operating.” To write ‘a tale of Morocco’ as I have, while keeping the country and its citizens firmly in the background, would be old-fashioned and ugly. At the same time, however powerful my imagination and deft my typing, I cannot know what it is like to be Moroccan. I’m on shaky ground writing Moroccan characters.

I believe passionately – and I trust this audience will excuse me – in my right to write. To imagine worlds and lives, and to explore them. In the case of The Sultan’s Emu, the novel’s inspiration and energy come as much from my own direct experience of how European colonialism works in the 21st century. That’s a story that needs telling, and I have the authority of the participant as well as the dreamer.

The diffident English official trying to find his place in the world is very close to home; the Belgian dancer was a bit more of stretch. But they were both born in my head, and I have explored their feelings and their deeds sincerely, if not infallibly. Indeed, I feel even less at home writing a western European woman than I do a Moroccan man.

But Eva the dancer is the reader’s essential companion through the novel: unlike the diplomats, in their confected worlds of words, she experiences life immediately and physically: Moroccan market alleys, the colonialistic manoeuvres of amorous men. If writers are only allowed to write what we have personally lived, all that’s left is autobiography.

And yet Africa and the Africans cannot be merely backdrop and puppets for other peoples’ dramas. To plunder the rich story-telling tradition of Marrakesh and the exotic charms of her streets for an English-language entertainment is intellectually as obnoxious as stealing away Africa’s minerals and lives for the benefit of European economies. And it can’t make for credible fiction.

So the people of Morocco, gathering for their morning tea in Marrakesh’s legendary market square and uncomfortable about all the foreigners, are significantly present, powerful and enduring in The Sultan’s Emu; I hope I have represented their world fairly. But I do not speak as them or for them.

The accounts of Abd-al-Aziz’s wild collection reflect European attitudes, not Moroccan: the novel inventories the attitudes, not the collection. In exploring how men do imperialist diplomacy, I found an uncomfortable overlap with how they do relationships and how they do narrative. The diverse motives behind the stories, veiling whatever the truth might be, are the real story.

As the schemes of the diplomats unravel, so too does our certainty about our tales. Fascinating and even tragic figure though he was, I do not instrumentalise Abd-al-Aziz. The Sultan remains, like his emu, a figure of ambiguous meaning and reality, trapped somewhere in his palace. We cannot know him or laugh at him, but we must try to understand what he tells us.

The Sultan’s Emu by RJ Wilton is available now.

See more about this book.

RJ Wilton was advisor to the Prime Minister of Kosovo in the lead-up to the country’s independence, ran an international human rights mission in Albania, and co-founded the Ideas Partnership charity supporting marginalized Balkan communities.

Robert has also written about researching his novels in The curiosities of history.

Images:

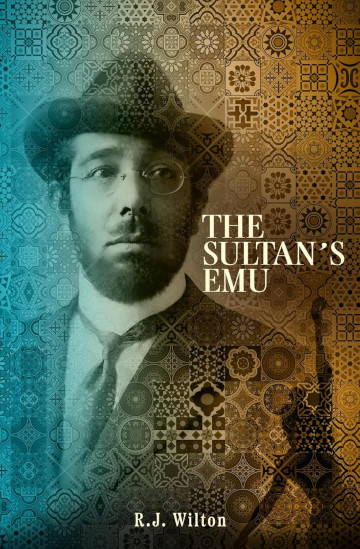

- Sultan Abd-al-Aziz, detail, La Vie Illustrée no 143, 12 July, 1901: Wikimedia (public domain)

- Circus trapeze artists, 1890: Picryl (public domain)

- Walter Burton Harris by Sir John Lavery, 1907: Wikimedia (public domain)

- Affiche de l’exposition coloniale de Marseille de 1906, poster: Wikimedia (public domain)

- Old photo of Jemaa el-Fna, Marrakesh: ernikon for Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)