When the Nazi occupiers of the former Czech province of Bohemia, in an act of revenge, obliterated the village of Lidice and killed or transported its inhabitants, they did so intending that its very name should be erased from history. Yet Lidice soon became a symbol of the horrors of fascism and its name was known worldwide. Catherine Hokin examines why the legacy of Lidice outlasted its destruction and why we still need to remember it.

Stop him! Stop him! Do not wait!

Or will you wait and let him destroy

The village of Lidice, Illinois?

From The Murder of Lidice by Edna St Vincent Millay

When I first began writing novels set in the shadow of World War Two, I came across a piece of advice directed at war correspondents which can basically be distilled down to the following maxim: keep it real, keep it human, keep it relatable.

That has stood me in good stead and it came to mind again when I was researching my latest novel, The Girl in the Photo, and more specifically the fate of the Czechoslovakian town of Lidice and the impact its destruction on 10 June, 1942, had on the wider world.

The Czech provinces of Bohemia and Moravia were occupied by the Nazis in March, 1939, and remade as a German Protectorate. Lidice, a village of around 500 inhabitants 20 kilometres west of Prague was one of that occupation’s worst – and deliberately most visible – casualties.

The village was an unremarkable if picturesque place. There was a small common edged by walnut trees and a river which supported a mill. The church of St Martin sat on a hill overlooking the main street which contained an inn, a grocer’s shop and a number of low roofed cottages.

The men who lived there were agricultural workers or miners and – until Hitler turned a vengeful eye on the place and ordered its complete erasure – the only local point of interest about it was the strength of its football team. And yet, in 1942, the name Lidice became international shorthand for the horrors of fascism.

The response to the village’s destruction was immediate and wide-reaching. It produced poems and novels, including the Millay piece. Several towns and neighbourhoods across the world, including in Joliet, Illinois, adopted the name Lidice as theirs.

The impact on mining communities was particularly strong – in Stoke-on-Trent, city councillor and later Member of Parliament Barnett Stross led a Lidice Shall Live campaign in direct response to Hitler’s orders that Lidice would die.

So why did this atrocity, which occurred in the midst of so many other equally heart-breaking atrocities, capture the world’s imagination in such a profound way?

The facts of what happened to Lidice are well-recorded. On 27 May, 1942, an assassination attempt was made in Prague against Reinhard Heydrich – the Acting Reich-Protector of German-occupied Bohemia and Moravia – by a group of Czech agents parachuted in from Great Britain.

Heydrich, who was known as the Butcher, was a deeply hated man. During his reign of terror, 5,000 anti-Fascist fighters were imprisoned. Around 400 were sent to the gallows without trial and at least 1,000 to the torture chambers beneath Prague’s Petschek Palace.

Heydrich survived the initial attack but died of his wounds on 4 June. His funeral in Berlin on the ninth was attended by Hitler on whose orders Lidice became the scapegoat for the murder.

The connection between the village and the assassins was tenuous to say the least. The Nazis viewed Bohemia and Moravia as a hotbed of resistance which they were determined to crush.

The first step was to find ‘evidence.’ This came in the shape of a vague letter in which one Lidice’s inhabitants seemed to be boasting about partisan connections.

The second was an act of brutal revenge. All 192 men – and seven women who wouldn’t be separated from their husbands – were shot. Another 205 women were sent to Ravensbruck.

Of the village’s 96 children, 81 were sent to Chelmno and gassed, with the reminder taken away for Germanisation.

Once that was done, Lidice itself was destroyed. Every building, and the town cemetery, was burned to the ground; every speck of the ashes and rubble that remained was buried. The site was left as bare as if the village and its people had never existed.

It didn’t work: 145 of the women survived Ravensbruck and some of its stolen children came home. In 1947, Lidice was rebuilt 300 meters from its original location. The original site now holds a memorial to the murdered townspeople and a garden filled with thousands of rose bushes connects the new with the old. And its name never vanished at all.

Like anything in history, the why is far harder than the what. Perhaps Lidice lived because this atrocity wasn’t kept secret. The destruction of the village was filmed by the Nazis and shown.

They also announced the village’s fate to the world via a brutally detached radio announcement broadcast the next day which stated that: “All male inhabitants have been shot. The women have been transferred to a concentration camp. The children have been taken to educational centres. All houses of Lidice have been levelled to the ground, and the name of this community has been obliterated.”

Or perhaps it was because, as Millay’s poem suggests, the true face of the enemy at everyone’s door had finally been fully revealed and feeling safe – feeling like the danger was a long way away – was a luxury nobody could afford anymore.

We turn to the personal to make connections, to empathise. Perhaps that in the end is why Lidice aroused such an outpouring of global support. The numbers of the dead were small enough to imagine faces. The village could have stood in for any British or American or European village. Lidice was real and relatable.

Or, as the British writer Harold Nicholson put it in an anthology written to commemorate Lidice’s fate in the aftermath of the tragedy: “The conscience of the world was outraged by this act of vengeance… the tragedy of Lidice marked, in the words of that Great German, Thomas Mann, ‘the gradual growth of an awareness of universal human responsibility.‘”

Let’s hope we don’t forget the village, or that.

The Girl in the Photo by Catherine Hokin, the third in her Hanni Winter series, is published on 27 January, 2023.

Catherine’s a generous contributor to Historia and has written a number of features linked to her books, including:

Concentration camps and the politics of memory

The Minister for Illusion: Goebbels and the German film industry

An appearance of serenity: the French fashion industry in WWII

The ‘hidden’ Nazis of Argentina

The Berlin blockade, 1948–9: the first Cold War stand-off

German reunification: still dividing opinion 30 years on

Images:

- Partial display of the Memorial to the Children Victims of the War, Lidice, a bronze sculpture by Marie Uchytilova in Lidice, Czech Republic by Michal Ritter: Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Lidice after the destruction by Nazis in 1942: Deutsches Bundesarchiv via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Lidice Memorial near Prague, Czech Republic by Adam Jones: Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

- Funeral ceremonies in honour of Reinhard Heydrich. Adolf Hitler pays tribute to the deceased, 9 June,1942: Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Lidice Memorial – Memorial to Child Victims of War by Marie Uchytilova, Near Prague, Czech Republic by Adam Jones: Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

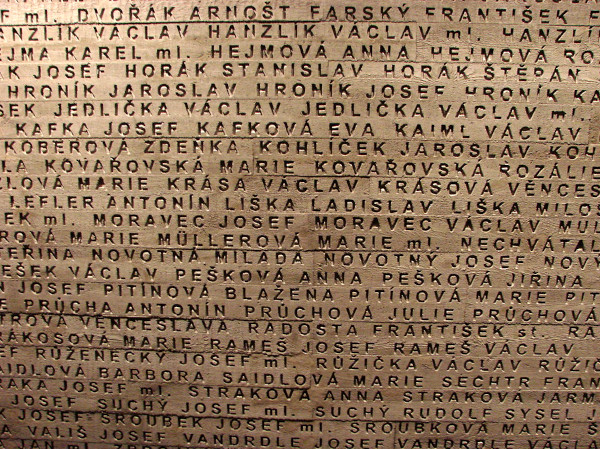

- Lidice Memorial – Victims’ Names on Wall, near Prague, Czech Republic by Adam Jones: Flickr (CC BY 2.0)