St Kilda Bird Song by KF MacCarthy won the 2024 HWA Dorothy Dunnett Short Story Competition. Our judges said: “A magical and immersive story of a late 19th-century teacher on the remote island, told from diverse perspectives with fluency and confidence. A very special piece of writing about a remarkable place.”

The 2025 Short Story Competition is open for entries until 31 July.

Unfurl a map of the world. Take your finger and place it on Scotland. Find Edinburgh. Then push up and west to Skye, then west again. Feel the paper hiss under the pad of your fingertip and keep going. Keep going and going for almost a hundred miles, your finger cutting through violent Atlantic waves, casting a looming shadow over the heads of minke whales. Stop. Can you see it? That speck. That pinprick sized mote by the ridge in your fingernail.

The archipelago of St Kilda.

One swift origami fold of the map and you’re a seabird, up high in the firmament above a churning navy sea. You hang in a vast blue dome, faintly divided by a bleeding line on the far horizon. Blue, blue, blue. It’s all your beady eye is filled with. Tilt your wings and swoop down with the other shrieking fulmars and bonxies, towards columns of sheer, slick rock slicing out of the waves.

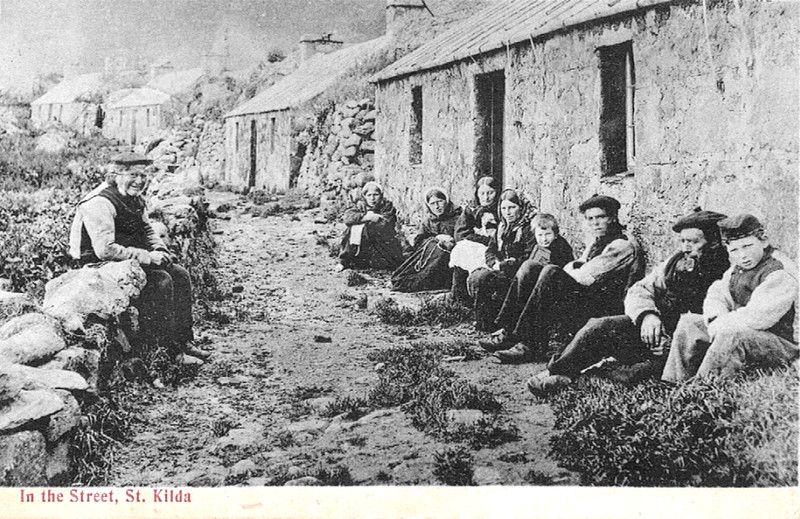

Descend closer still. The largest island, Hirta, is a shallow bowl tipped over to let in the sea at a sandy bay. There are no trees — there is no word for tree, here — only close-cropped grass and venerable sheep. Behind the bay, against all logic: a row of squat houses.

Dive down and spin through the air. You don’t want to be a fulmar here. You’ll end up salted in a barrel. They’ll make a nail of your beak, an espadrille of your neck, a bottle of your stomach. They’ll use the oil in your belly to light their lamps.

You could instead be a cleit. A boulder. A grassy hollow. You could be anything at all. This is a place where a cove has a memory, where a stream hears what you tell it. There is a soul in every thing.

Your wings corkscrew like a twirling magician’s cloak and in a puff of feathers, you’re a common moth, buffeted by the smack of a strong gust. Down a chimney you go and into a cave-dim room, singeing your wingtips on the fire before tumbling to the ground. Warmth. Loud chatter, some singing. Several pairs of bare children’s feet miss you by inches. You’ve arrived in the midst of a gathering. You flit towards a window, cling to a curtain fold. Here, so far from humanity you might as well be on the surface of the moon, are the most unlikely of things. People.

There are 77 of them. There used to be more.

15th September, 1884

My dear friend,

It’s past midnight, and light and paper are scarce, but I find it comforts me to write. To remember there is a world beyond the horizon.

I imagine you in your cosy office with the leather armchair by the fire. You must imagine me sitting on a rickety chair at a low table, with the rain lashing outside and the wind playing through the lintel like a reed instrument. I’m not yet used to the nights here. I wonder whether any islanders are awake to see the lamp flickering in my window. It’s a beacon advertising my wakefulness. Worse, it’s a profligate waste of fuel.

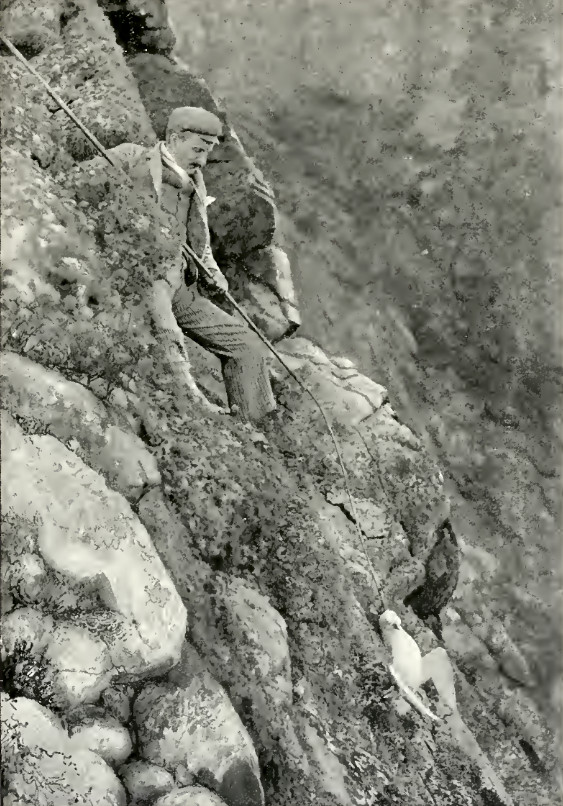

Three months into life as the first dedicated schoolmaster on St Kilda. I hardly know where to begin. I’m holding up well. You know me as a man of daring and resilience, I think (I hope), and I am certainly putting those qualities to good use here. I have had several near-death experiences already. In fact, over summer I averaged about one per week. I’ve been taking part in the ceaseless, herculean effort required to survive here. Snaring fulmars and puffins, dangling off cliffs attached to a rope. Catching sheep. Fishing in some pretty lively seas. And of course teaching every weekday forenoon, which is what I was put here to do.

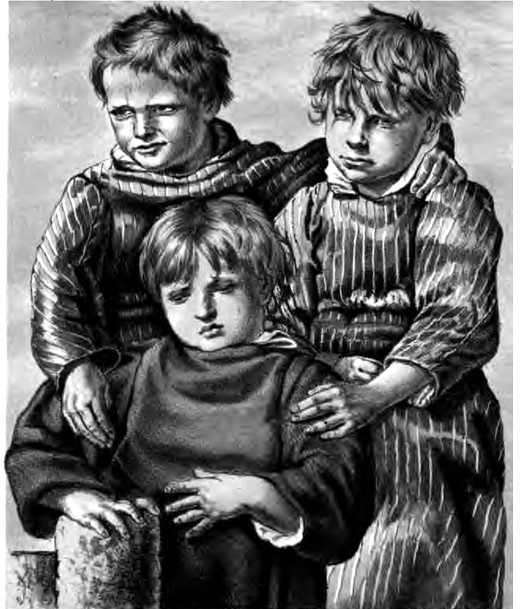

My students are making excellent progress. There are ten of them, ranged in age from five to eighteen. I’ve been tasked with teaching English, although I can converse perfectly well with them in Gaelic and they’ve also taught me a few Norse words. The brightest among them is a young man named Alexander Ferguson. I intend to leave my books behind for him when I go.

I’ve been welcomed warmly, in the main. The people are stout, generous and instinctively kind. There is one fly in my ointment. The Reverend John Mackay. All other hardships are bearable but I’m finding him a challenge, shall we say. The old man has been here some twenty years and is master of his own little dominion, as engrained in this community as the guano on the cliffs. I suppose the remoteness of location attracts a certain kind of character. Where I sought adventure, he sought something else. But enough on that. I’m dyspeptic after my supper of preserved eggs and to think on him further will make me bilious.

A note on the food. Everything here comes with a side of seabird. I witnessed the great annual massacre of fulmars in August. They were piled up higher than a house and the place was swirling with feathers. Every part of the bird is put to use but the oil is most revered. The islanders evangelise about the healing properties of this sticky, foul-smelling stuff. Worst of all, they add great spoonfuls of it to porridge and declare this oleaginous substance the finest breakfast in all Christendom. I am frequently hungry.

My lamp peters out. I shall tuck this letter into the pile along with all the others I can’t send. No hope of a boat until April.

Your devoted friend,

Dr Kenneth Campbell.

***

You are a wooden cradle. Smooth with the feet and hands that have rocked you, carrying along your spine the imprint of the tiny souls you’ve held. The air in the shadowy room is close. Peat, smoke, blood. A woman struggles in the narrow space between life and death. You see the rounded rump of the crouching knee woman, the bramach-innilte. You see feverish cheeks, a dark tendril of hair plastered to a pale forehead. The struggle is long. Sunset. Sunrise. At its end is a gargled cry, repeating the refrain of the gulls outside. ‘I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive.’ The sway of dun tweed skirts over compacted earth. The knee woman takes a bird-stomach bottle from a shelf, turns it in her hand. She keeps her secrets close, bars all others from the room, but you see her do this. She anoints the cord with fulmar oil. Later, the delight of a bairn’s spine along your spine again. Lachlan, mo chridhe, says the woman who gazes down. Lachlan, my heart. Chubby fists escaping their swaddling, sharp-nailed fingers playing at your sides. An absentminded toe on your rocker, the swish-swish and the fire crackling.

***

My dear friend,

I have noticed lately a division between the village and the manse, where the Reverend lives with his elderly sister and his housekeeper Ann MacDonald. Whenever I go to the manse for dinner, there is always some gossip offered at the table. I never comment, preferring to keep well out of such matters. But you can imagine how it is, in such a small place. Everything seems to close in and strife is intensified. The lady Ann MacDonald has quite the sharp tongue and she relishes cutting those she dislikes to ribbons with it. Likewise, Mackay favours certain islanders and castigates others. He says that though his influence has caused ‘a change for the better as to their moral character’, there remain pockets where Satan rules. What nonsense.

I thank God every day that I am able to converse fluently with the people in their own language. They have the truth directly from my mouth, and I the truth from them, and like this we understand each other. I’d rather spend my time in the village and take my meals among the families there. A third of the population left for Australia thirty years ago and those they left behind often ask me to write letters. They dictate them to me around the fire. It’s a pleasant way to spend an evening.

***

You are the font in the new church, absorbing the cold. Close by, the Reverend is spouting his booming invective. Infecting the air. His leaden words press the people down into their pews, pool in the hollow of your basin. ‘And the angels shall CAST them into a FURNACE of FIRE.’ A fleck of spittle flies, lands in his grey whiskers. ‘There shall be WAILING and GNASHING OF TEETH.’ How silent it is, when he isn’t here. How peaceful. Mrs Gillies, dowager, suppresses her sneeze in a handkerchief. The chill seeps from a pinewood pew into the meagre fat around Euphemia’s hips until they are numb. The Reverend, a billy goat armed with the word of God, stamps his foot. The shockwave passes through your pedestal. Irritating.

***

There is a terrible plague of infant deaths here. I was speaking with Mackay about the lack of young children. He said that when babies come to the age of seven or eight days, ‘they generally die’. Generally. As though it is accepted and unstoppable. They’re afflicted with lockjaw, he said, which the islanders call the ‘eight-day sickness’.

Being a trained doctor myself, I asked if I might assist at Mary Mckinnon’s labour. Mackay told me in no uncertain terms that I was not to interfere. Mrs Mckinnon gave birth to a boy, Lachlan, on the first of the month. The women said the date was a good omen. Then we watched on helpless as he sickened.

There was very little I could do for him. Several times, I fed him a few drops of wine in water on a spoon. He fixed his sea-blue eyes on me and looked at me intently, as though asking a question. On the seventh day, his jaw slackened. On the eighth, with appalling inevitability, he died. I don’t know how the parents bear it, to see any increase in their family stymied in this way. Siblings born one after the other go into the same graves. There’s a man here told me he’s lost nine children. And with every infant death, hope for future generations is diminished.

Forgive me. I have blathered on. I have too much time for rumination and too few to confide in. I hope to post these letters soon, when the first steamer lands, and to have news of you.

***

You are the church font, absorbing dank sorrow into your stone pores. In the front pew, the mother stifles her whimpering sounds, the father twists his cap in his hands. The dour Reverend’s voice falters, this time. He is moved. ‘Man flourisheth as a flower in the field. For as soon as the wind goeth over it, it is gone, and the place thereof shall know it no more.’ Forevermore, you think. The place thereof shall remember it forevermore.

You are the wooden cradle. Stripped of your bedding. Put amongst crates and ropes in a drafty storage cleit. Too short, it was. You were attuned to his every sound and move. The warm weight of him. For a while, you dream phantom cries.

***

I made it out the other side of winter. Just about. The tempests here are a crashing disturbance in the brain, enough to drive a man half mad. I’ve seen roof tiles blown off in gales and driven into the earth like axe blades. And the endless, malicious rain. It falls in sheets.

Norman Gillies showed me how to ascertain from the flight patterns and calls of birds when a storm is heading our way. He’s always right. When it’s bad, the children are carried bodily to school by their parents so they aren’t blown off the edge. Several sheep meet this fate every year. I learned that the verb ‘to die’ on Hirta translates as ‘to go over it’.

We’re past the worst of it now. The oystercatchers arrived this week, and with them the stirrings of spring. We’ve had four days without rain and even a spell of sunshine! In such sultry weather, when I can roam about the place, I feel the luckiest man on earth. It has done something to me, to see big skies every day. In Edinburgh, you see slivers of the heavens between buildings when you crane your neck to look up. But how often does one look up? We are here so briefly and we see such little of the wondrous world.

***

You are a blade of grass. Bending in the wind on Conachair, a dizzyingly high peak. The land shears away below and the sea stretches in every direction, into eternity, reflecting glittering sunlight like a dimpled pane. Over to the east, a pod of dolphins. The sky has been cloudless all day. Blue, blue, blue.

The teacher came to sit here earlier. He laid down his jacket and reclined over you. Thrilling to feel anything other than pummeling rain or the hard pinioning of a sheep’s foot. It went dark and you felt the pressure and warmth of his back. You heard his thoughts. He was saying, ‘God created every living thing with which the water teems and every winged bird according to its kind.’ He was all joy for a moment, thinking of the miracle he looked upon and how it came to be. But he couldn’t let his pure thought of God go unstained by that which followed, of the Reverend John Mackay. His whole being became sour. A single rotten apple infects the whole barrel. Then his thoughts turned inwards. To his own intrusion into something unspoiled. When he left, it took you hours to stand up. Now the sky is melting into a thousand streaked colours. Lurid pinks you’ve never seen anywhere else. Down by the houses is a line of people. A long line, processing steadily along the shadow of the setting sun, and at its head a coffin fit for a lamb.

***

You are the lover’s stone. A tall pinnacle worn by rain and scrambling feet, infused with the same question repeated over centuries. ‘May I have her for marriage?’. You almost always give your blessing.

You are the Great Auk’s egg. You have no notion of what an ornithologist is. You merely exist as you are, delicate marbled casing around a ribcage around a beating heart. Impassive. The size of an outstretched palm.

***

May God preserve me. I have exchanged cross words with Mackay. When I told him I planned to leave my books behind for Alex, he spoke rudely to me and told me I would do no such thing. He went further and forbade all teaching materials other than the Bible. No poetry. No history or natural science. I despair. The man is a hindrance to the progress and happiness of the people.

Unfortunately, they are in his thrall. I am just returned from the third interminable sermon of the Sabbath. The third! The islanders were gifted a heater for the church but decided it shouldn’t be used- Mackay encourages discomfort. He is a hair-shirt type of man- and it now sits rusting cheerfully on the ground outside. My posterior is positively numbed. He has also deemed it sinful to laugh, smile, play games or do any kind of work on the Sabbath. I am forced to attend his sermons, for if I didn’t I would be shunned, and so I curse my gloomy Sundays. The so-called ‘day of rest’!

***

You are the discarded church heater. A symbol of mortification, slowly eroding out of usefulness. What’s so wrong with comfort, you wonder, as the grass grows tall around you.

You’re a shelter made of stacked stones, standing sentinel with the others in Gleann Mor. Ancient. A decade passes in a blink. Warm currents of the past are borne on the breeze and they slip through your gaps, play through the upturned ribs of a nearby sheep’s carcass. Only you know how old you are. You’re a clue. A trace. But a memory stirs deep within you. A time when fire made your walls glow warm and sinless people slept under your roof.

***

13th June, 1885

My dear friend,

This will be my final missive from St Kilda. I leave in a fortnight.

I have wondered at what I have achieved, though the Ladies’ Association have written to say they are pleased with me. They asked whether I would consider staying on another year. If it weren’t for Mackay, I might have.

Having been cut off from humanity for eight months, since April we have received multiple steamers. They bring supplies, mail and tourists, who really are a menace. One just went by my window, parasol in hand, and peered right at me. The islanders do a roaring trade in tweed and mittens, which they lay out on their doorsteps as soon as they see a mast on the horizon. They have sensed their opportunity and now ask for money for the smallest transaction, capitalism being a relatively new concept to them. The more this place is exposed to mankind’s so-called civilising influences, the more it is corrupted. I include myself in this. Tourists have taught them greed and brought over illness. Mackay has taught them shame. I have taught them, of all impractical things, rudimentary English.

I will miss my students and the friends I’ve made. When they wave me off on the shoreline it may well be my last sight of them on this earth. But I sense I have intruded too long. Now that I have determined to leave, I’m engulfed by a wave of homesickness.

I wish the next schoolmaster luck. He will need it! And if I never see another preserved egg it will be too soon.

***

You are the moth again. Inside a low-ceilinged room at the teacher’s farewell gathering, clinging to the fold of a short curtain.

The singing is loud. ‘Hymns only. Forget the old songs’, Mackay decreed years ago. But he’s not here to object. He declined the invitation and sits in the manse, brooding. The dancing thrums through your body. You witness the whisky taken out from the wall and passed round. The honour of mutton, cooked especially. The door is thrown open. It frames the view over Village Bay, casually astonishing.

The teacher entrusts his books to the boy called Alex. ‘No need to tell him. Keep them close’, he says. Then, ‘Keep this. And these. You’ll get more use from them than I.’ Steadily emptying the packed trunk, handing out pencils and tobacco and his best coat.

Nearly midnight, the gloaming fading fast. You can perceive the spinning of the world here. The full moon is a full-beam spotlight reflecting pearlescent off the sea. A girl sings the final song. The Bird Song. She mimics the wheeling and whistling of seabirds. The verses their chattering, the chorus their calls. Hion dail a horo hi! Hion dail a la! How can anybody make such a sound? It flows from her ancestors out of her mouth. She sings it as a gift.

You take off and lurch towards the open door. In a puff of powder from your wings, you twist and you’re a fulmar. Up you go into a vast navy canopy speckled with stars, leaving the row of houses and the people within them far beneath you. Getting smaller. Disappearing. A speck, a pinprick sized mote. But the girl’s song goes on, soaring up with you.

Ho ro hi! Ho ro hi!

You join in. I’m alive! I’m alive!

Snatches of a joyful song, borne away on the breeze.

Historical note by the author: Dr Kenneth Campbell, the first dedicated schoolmaster on St Kilda, was present on the island at a time of great change. Only 45 years later, the people would vote to be evacuated to the mainland. His obituary states that he was a man of “grit and perseverance” and “a delightful raconteur of his reminiscences of… St Kilda”.

For thousands of years before the islanders were exposed to organised religion, they adhered to animism, a belief system in which all living and non-living things are thought to have a spiritual essence or soul.

It has been posited that the ‘eight-day sickness’ (tetanus) could have been caused by the fulmar oil used to anoint umbilical cords or by its storage conditions; 61 per cent of all babies born on St Kilda between 1856 and 1891 died within the first 27 days of life.

The traditional St Kilda Bird Song, after which this story is named, is preserved on the album Treasures of Scotland (1987), sung by Joan Mackenzie. A lively reinterpretation can be heard on Garefowl’s Cliffs (2020).

KF MacCarthy is a writer from South Yorkshire. She has been shortlisted for the Bournemouth Short Story Prize and the Alpine Fellowship’s Academic Writing Prize, and was longlisted for the Historical Writers Association Dorothy Dunnett Short Story Prize in 2022.

Her debut novel-in-progress tells the untold, interwoven stories of marginalised women in Quattrocento Florence. It won the Farnham Literary Festival’s First Five Thousand prize in 2024 and was longlisted for the Cheshire Novel Prize in the same year. She’s researching a second novel set in a similar time and place, which uncovers another little-known story from the High Renaissance.

She’s on Instagram.

See more about the six HWA Dorothy Dunnett shortlisted writers.

You can buy the six best stories from 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020 and 2019 as ebooks or print-on-demand paperbacks.

The 2025 Short Story Competition is now open for entries until 11.59pm on 1 July.

Read the stories that won the HWA Dorothy Dunnett Short Story prize in past years:

2023: Hecate’s Daughter by Jo Tiddy

2022: Collapse by Chrissy Sturt

2021: His Mother’s Quilt by Naomi Kelsey

2020: The Race by Alice Fowler

2019: The Daisy Fisher by Kate Jewell

2018: Nineteen Above Discovery by Jennifer Falkner

2017: A Poppy Against the Sky by Annie Whitehead

If you’d like to know some more about the history of St Kilda, you may enjoy reading Two strands of lost history from Scotland by Elisabeth Gifford.

Images:

- Birds over Boreray island, St Kilda archipelago: Leyzif2000 for GoodFon (public domain)

- Map of the St Kilda archipelago: Eric Gaba (Sting) for Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

- St Kilda Children from St Kilda Past and Present by George Seton, 1878: Internet Archive (public domain)

- Ferguson fowling on Borrera from With nature and a camera by Richard Kearton, 1898: Internet Archive (public domain)

- Dividing the catch of fulmar, St Kilda by George Washington Wilson (detail), c1886: University of Aberdeen Photographic Archives (CC BY 4.0)

- Grandma’s Darling: Library of Congress via Picryl (public domain)

- Cemetery with Bagh a’ Bhaile or Loch Hiort beyond by Russel Wills: Geograph (CC BY-SA 2.0)

- St Kilda, Hirta, Village Street, view eastwards by Rob Farrow: Geograph (CC BY-SA 2.0)

- St Kilda, looking over the village towards Conachair by M J Richardson, 1967: Geograph (CC BY-SA 2.0)

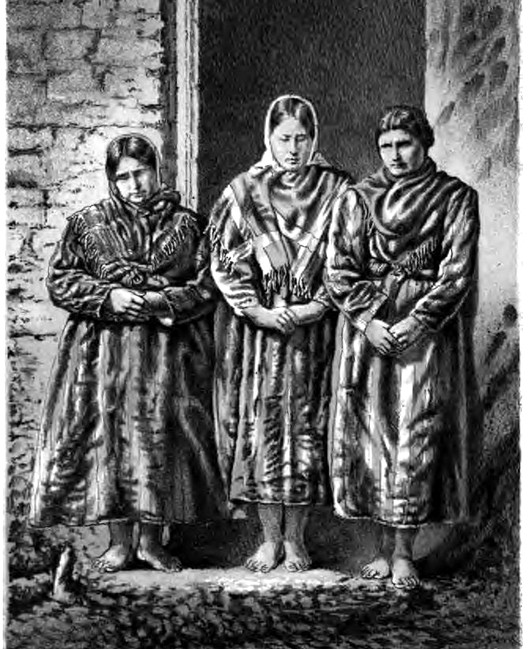

- St Kilda Women from St Kilda Past and Present by George Seton, 1878: Internet Archive (public domain)

- St Kilda Landing Stores from St Kilda Past and Present by George Seton, 1878: Internet Archive (public domain)

- In the Street, St. Kilda, postcard sent in July, 1903: Wikimedia (public domain)