Sulky, brutal Achilles; vain, passive Helen. Have we misjudged these characters from the stories of the Trojan War? Susan C Wilson, author of Helen’s Judgement, argues that we need to go back to the Iliad to understand them, and appreciate the importance of the concept of shame, which drove the Ancient Greek heroes and heroines.

Achilles and Helen are two of the Ancient Greek bard Homer’s most complex characters, yet we moderns doggedly interpret them as shallow. Helen, whose adultery with Paris provided the casus belli for the Trojan War, is judged as a mirror-gazing, passive beauty. Achilles, meanwhile, is the warrior who, following a tiff with the commander-in-chief of the Greek army, storms off to his shelter and refuses to rejoin his brothers-in-arms.

My new novel offers a different perspective on both characters by remaining faithful to their oldest surviving versions: those of Homer’s Iliad. Although Helen’s Judgement takes liberties with plot, it explores the motivations and personalities of Helen and Achilles in keeping with their reactions to their Iliadic predicaments and heroic shame culture.

Helen appears just six brief times in the Iliad, including two occurrences of double consecutive scenes, whereas Achilles is the lynchpin of the poem.

The Iliad begins with an invocation to the goddess to sing of Achilles’ anger and ends with Achilles returning the corpse of his most hated enemy (not Agamemnon but Hector). The classicist Robert Graves even named his interpretation of the Iliad ‘The Anger of Achilles’.

Yet, despite her lack of word count, Helen holds herself responsible for the whole sorry story of the Trojan War. She wishes she had died at birth or at least never married Paris (scene VI:312-368).

True, Helen is preoccupied by how others see her, but this is in respect to her conduct and the conduct of Paris, not her beauty. When the goddess Aphrodite coerces her to sleep with Paris, she frets about what the Trojan women will think (III:395-461). She deplores Paris’ alleged inability to see how despised he is (VI:312-368). Racked with remorse, she pines for her former home, family and friends (III:121-180).

A more cynical interpretation could, of course, be made. Perhaps Helen is seeking pity when she berates herself. Perhaps she draws comfort from self-pity. And perhaps, if she is seen to be tormenting herself, others might not feel the need to inflict a worse punishment.

As for Aphrodite, is she a manifestation of Helen’s conflicted sexual desire?

I see no reason not to take Helen at, mostly, face value, without accepting her belief that she and Paris were the sole reason for the Trojan War.

Achilles’ behaviour is more challenging for a modern audience. In part, our disgust for slavery makes it difficult to sympathise with his anger over Agamemnon commandeering his human war-prize, the action that provokes Achilles’ withdrawal from battle.

Additionally, a chasm gapes between Homer’s ideal of individual glory in combat and our more familiar ideal of the unit (see, for example, the British Army’s values of loyalty and selfless combat).

To understand Achilles, we must consider him in the context of his culture. If we accept the concept of shame cultures and guilt cultures, modern westerners might broadly be said to live in a guilt culture influenced by Judeo-Christianity. Social order is maintained through the individual’s private conscience and the anticipation of punishment for breaking rules.

Conversely, in the shame culture of Homer’s elite warriors, the perception of peers defines an individual’s value. War-prizes, awarded by those peers, are the proof of a warrior’s worth.

We could compare modern-day social media, where online peers reward the carefully curated output of other users with likes — or disregard it with an absence of the same. A user might face the public shaming of a ratio or might withdraw after a pile-on.

To win affirming ‘likes’, the Homeric hero must shine as an individual, not as a team member. Homer gives each of his greatest heroes an aristeia, a warrior’s most outstanding episode, where he single-handedly outperforms everyone else on the battlefield.

The celebrated noblesse oblige speech by the Trojan ally Sarpedon explains why elite warriors fight at the forefront of their men. By taking more than their share of the danger, they are seen by their subjects to justify their privileged lives. Their actions will enhance their reputations or the reputations of those brilliant enough to kill them.

Kleos, renown, is what compensates the warrior for dying prematurely. Achilles, in keeping with this value, strives to win it. The seizure of his war prize, Briseis, is more than a mere bruise to his ego. It is a haemorrhaging of reputation in a culture where reputation is everything.

His peers recognise this and do not condemn his decision to withdraw from battle… at least, not at first.

Achilles does claim to possess finer feelings for Briseis. He remarks that “every sane and decent man loves his own and cherishes her, as I loved her with all my heart, though but a captive of my spear” (scene IX:307-429). But the insult, and his reaction, would have been the same if Agamemnon had seized an inanimate object instead of a living woman.

His comrades’ attitudes change after Agamemnon, despairing at Greek losses, offers fabulous reparation if Achilles will return to battle. But Achilles has had a remarkable change of heart towards heroic values. In keeping with his later appearance as a shade in the Odyssey, where he says he would rather be poor and alive than ruler of Hades (scene XI:465-540), Achilles questions whether an undying reputation is better than being alive right now.

He has risked death for the return of another man’s wife, and the brother of that man showed his ingratitude by seizing Achilles’ ‘wife’. Achilles refuses to be tricked again.

He despises the compensation offered by Agamemnon, who he claims has achieved less in battle but takes the lion’s share of booty. Rewards, he has discovered, go to those who strive and those who do not, and both types die in the end just the same.

Why exchange his life for the kleos he no longer believes in?

He is unique in such reflections. The heroes relaying Agamemnon’s offer still cannot understand why he would be stubborn enough to turn down seven tripods, twenty shining cauldrons – and much more – plus the opportunity to become Agamemnon’s son-in-law.

Their former comrade, the traditional hero turned subversive, has never been more alone.

Helen’s Judgment by Susan C Wilson is published on 20 March, 2025. It’s the second of her House of Atreus books.

Find out more about this book.

susancwilson.co.uk

Instagram

Twitter/X

Bluesky

You may also enjoy Susan’s Motives of a Bronze Age murderess, in which she writes about Clytemnestra, Helen’s sister, and the main character in her first novel.

Related Historia features include:

The Trojan Wars: men or myths? and

The triumph of Greek myths and the destruction of a civilisation by Hilary Green

Women of the Trojan War and

Troy: an ancient story for a modern age (exhibition review) by Emily Hauser

And, for fun: Beware of Greeks: when Homer meets Holmes by Peter Tonkin

Images:

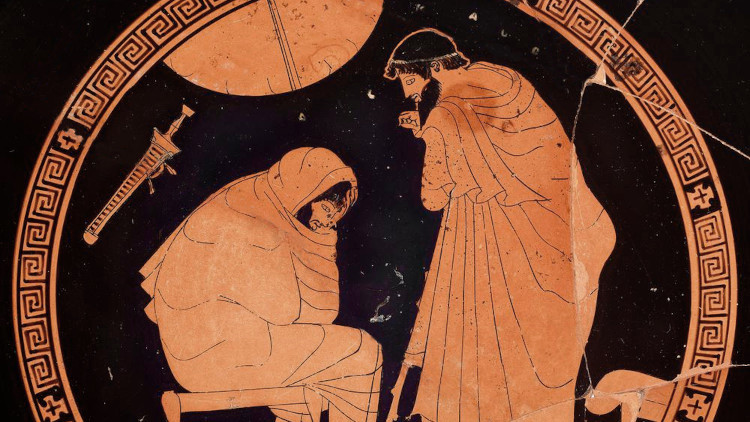

- Achilles (L, in his tent, armour hung up) and Odysseus, red-figured cup: © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- Helen boarding a ship for Troy, fresco from the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii: Wikimedia (public domain)

- The meeting of Helen and Paris, fresco from the Black Room in Pompeii: Chappsnet for Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

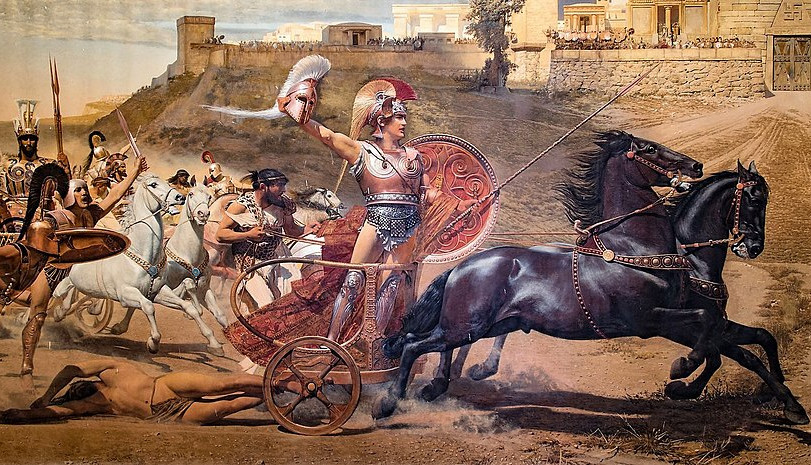

- The Triumph of Achilles (Achilles drags Hector’s lifeless body past the gates of Troy) by Franz von Matsch, 1892: Eugene Romanenko for Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

- Briseis taken from Achilles (L), fresco from Pompeii: Naples National Archaeological Museum) via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Achilles (R), wrapped in a himation, as Briseis is taken away from him, red-figured kylix: © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)