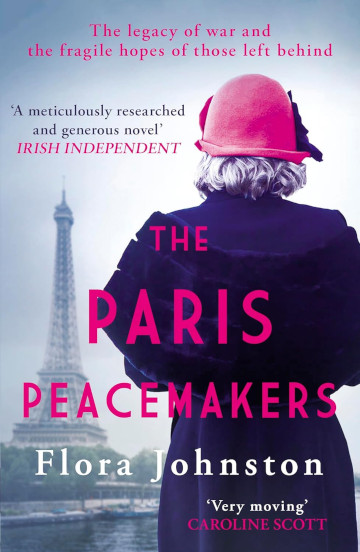

How, in 1919, could nations come together to begin rebuilding a world shattered by war? The answer seemed to be the Paris Peace Conference, which put together a plan which led to the Treaty of Versailles and what turned out to be a flawed and fragile peace. Flora Johnston’s great-aunt was a typist there, and from her family she drew the inspiration that became her novel The Paris Peacemakers.

We think of Remembrance Day as marking the end of the First World War. That’s true, but when the armistice was signed on 11 November, 1918, it was just that – an armistice, a ceasefire on the Western Front. Fighting still raged in the Baltic and Russia, and there was a very real possibility that war with Germany would break out once more.

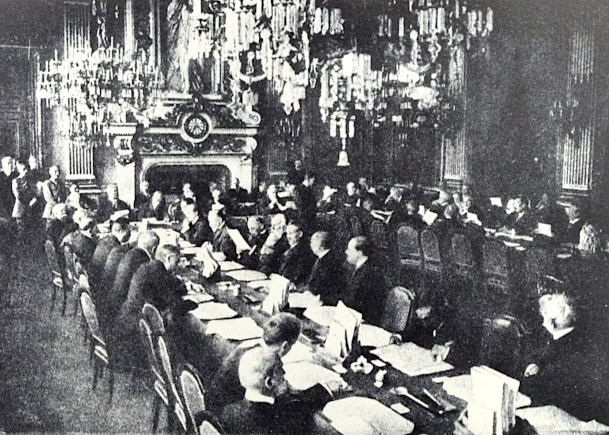

It was in this context that hundreds of international politicians, journalists, campaigners, and an army of secretarial and support staff began to descend on scarred yet still glamorous Paris in December 1918 for the Paris Peace Conference. Could they rebuild the world they had shattered?

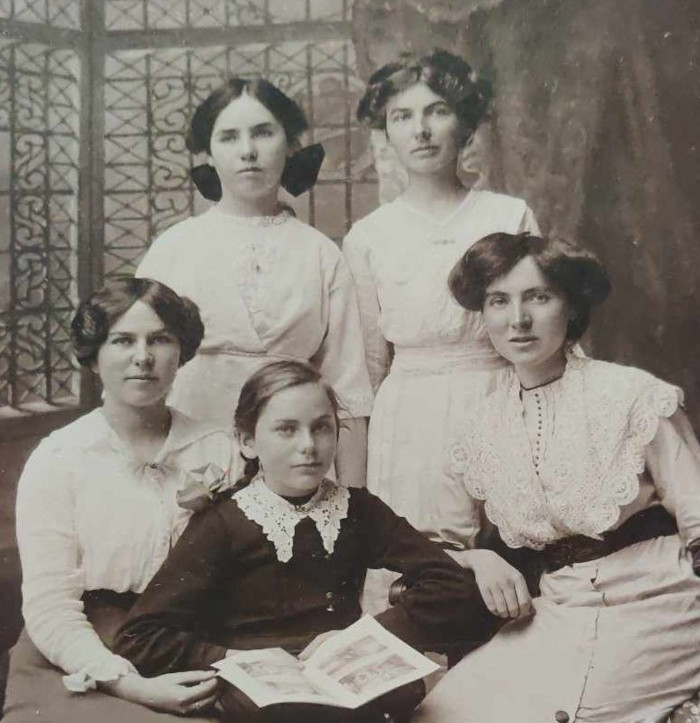

Among them was Mildred Keith, a young woman from Thurso on the most northerly coast of Scotland, who was there as a typist. She was my great-aunt, and the letters she wrote home to her mother from Paris became the inspiration for my latest novel The Paris Peacemakers.

Those who participated in the negotiations, whether as main players or in a supporting role, had themselves been damaged by four years of war, grief and trauma.

Perhaps that’s partly why the sense of hope and idealism with which the conference began was replaced so quickly by national self interest, revenge politics, and a strong desire to keep power in the hands of those who had created this mess in the first place.

Negotiations (from which Germany and Russia were excluded) continued on for long weary months, leading to the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in July 1919 and a series of subsequent treaties which together redrew the map of the world.

Decisions taken during the Paris Peace Conference had profound implications not only, as is well known, for the rise of Hitler and events of the 1930s, but also for the future of the Middle East, of Africa, of Asia and of eastern Europe.

One thing which surprised me during my research was just how many people, at the time, realised that an opportunity had been missed and the settlement would fail to bring lasting peace. Our world continues to deal today with consequences of decisions taken in Paris just over 100 years ago

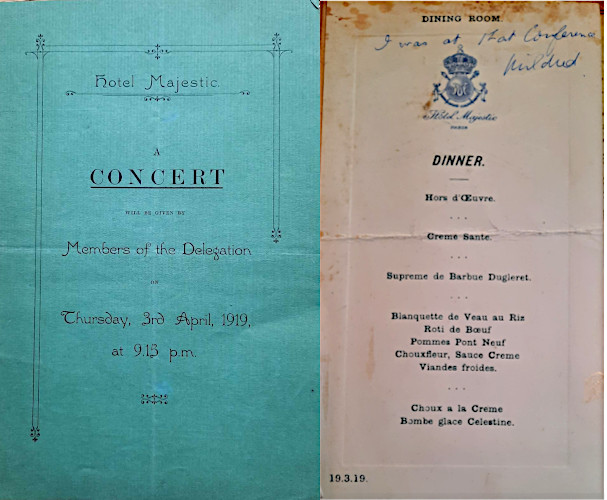

But back to Mildred. After four grim years of war she found herself living in luxury in the Hotel Majestic (now the 5-star Peninsula Paris), rubbing shoulders with the most powerful people in the world. Her letters home don’t speak about the detail of her work, because that was forbidden, and nor do they contain any scandal – she was writing to her mother after all!

But what they do offer is a vivid picture of Paris at the time, and of some of the frustrations she experienced. Mildred had a university degree, but like the other typists at the Peace Conference she was expected to be grateful for the role she had while men of equivalent education carried out far more interesting work.

One newspaper article stated quite openly that only attractive women were chosen to go out to Paris with the British Empire Delegation: the male delegates were leaving their wives behind for many months and some pretty female company would oil the wheels of the negotiations nicely.

Mildred’s older sister, Christina, not only had a degree but was a university lecturer in Classics at a time when that was highly unusual for a woman.

As the war ended Christina was also in France, based in Dieppe where she was teaching soldiers as part of the YMCA army education scheme. She left a memoir of her time there which I have previously published (War Classics: the remarkable memoir of Scottish scholar Christina Keith on the Western Front, 2014).

We are familiar with women nursing in France in 1914–9, but Mildred and Christina demonstrate that there were other forgotten roles for women during this fascinating period. Their lives and experiences inspired me to create their fictional counterparts, Stella and Corran Rutherford, and to write The Paris Peacemakers.

A third strand in the novel tells a different story of trauma and recovery after the First World War. Corran has a fiance, Rob, who played rugby for Scotland before the war. Through his story I explore the fate of the pre-war Scottish rugby team, a group of young men on the brink of adulthood who were swept up in war fever and mown down in battle.

Rob is a fictional character but all the other rugby players mentioned are the real young men who played for Scotland. Many of their names now appear on the war memorial at Murrayfield Stadium in Edinburgh.

The novel opens with the Calcutta Cup match between Scotland and England in March 1914, Scotland’s final international match before the war. Of the 30 young men from both sides who took to the field, mercifully unaware of what lay ahead of them, almost half were killed.

I became fascinated by the relationship between sporting glory and war, and by the question we still wrestle with today, of how to honour the men who died while standing against the sheer human waste of war.

During the course of my research I discovered the little known story of John MacCallum, Scottish rugby captain and at the time Scotland’s most capped player, who was jailed as a conscientious objector and spurned by the rugby community, and I wanted his choice and its consequences to be honoured too.

The Paris Peacemakers is a book about the fragility of peace and the appalling consequences of war. As we commemorate another Armistice Day more than a hundred years on, we see the same patterns of violent conflict, revenge and generational harm playing out around the world. How desperately we need peacemakers today.

The Paris Peacemakers by Flora Johnston was published on 18 April, 2024. The paperback edition came out on 24 October, 2024.

Flora Johnston worked for over 20 years in museums and heritage interpretation, including at the National Museum of Scotland, which has greatly influenced the historical fiction she now writes. She studied at St Andrews University and lives in Edinburgh. The Paris Peacemakers is her second novel.

florajohnston.com

@florajowriter

See more about this book.

Read Historical fiction’s role in giving a voice to women, Flora’s feature about the background to her first novel, What You Call Free.

You may also be interested in It’s time to remember Ganga Singh: maharaja, reformer, statesman by Alec Marsh, which looks at one of the signatories to the Treaty of Versailles.

Images:

- The Four Military Representatives of the Supreme War Council, Versailles, their CO’s, Secretaries, and Interpreters in Session by Herbert Arnold Olivier, 1919: Imperial War Museum Art.IWM ART 4214 (IWM Non-Commercial Licence)

- The Keith sisters from Thurso shortly before the outbreak of war. Mildred is back left and Christina front right: © Flora Johnston

- Mildred’s concert programme and menu from the Hotel Majestic: © Flora Johnston

- The first plenary session of the peace conference, held in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Paris, on January 18, 1919, L’Illustration Magazine, 25 January 1919, pp88–89: Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

- The Scottish rugby war memorial at Murrayfield: © Flora Johnston