Victorian women who killed have fascinated writers for over a century. What made the ‘angel in the house’ — a popular idea in the late 1850s — behave like a devil? Especially if they seemed, well, ordinary. Lesley McDowell, author of Love and Other Poisons, wonders what an ‘ordinary’ murderess was.

“[She was] an ordinary, good-humoured, capable woman with nothing sinister about her.”

George Bernard Shaw on Madeleine Smith.

Is there such a thing as an ‘ordinary murderess’, and is that what Madeleine Smith was, when she stood trial for murder in 1857?

Certainly the great Victorian novelist George Eliot found Madeleine “the least fascinating of murderesses”. And in her 1976 book, Victorian Murderesses, Mary S Hartmann agreed with Shaw, calling Madeleine an ‘ordinary (woman) who found extreme solutions to ordinary problems.’

Yet this ‘ordinary’ young woman of Blythswood Square, Glasgow, who was accused of poisoning Pierre Emile L’Angelier with arsenic in March 1857, had also been conducting an illicit affair with him for two years.

It was a clandestine relationship because Madeleine, the 20-year-old daughter of a wealthy architect, was materially and socially far beyond the expectations of a 36-year-old Jersey-born clerk. When she eventually became engaged to someone more suitable, and asked Emile for the return of her sexually explicit love letters, he threatened her with exposure to her father.

After repeated threats from him, Madeleine made three purchases of arsenic in February and March, and on March 23rd, Emile died from a massive amount of the poison. Just one week later, Madeleine was arrested for his murder.

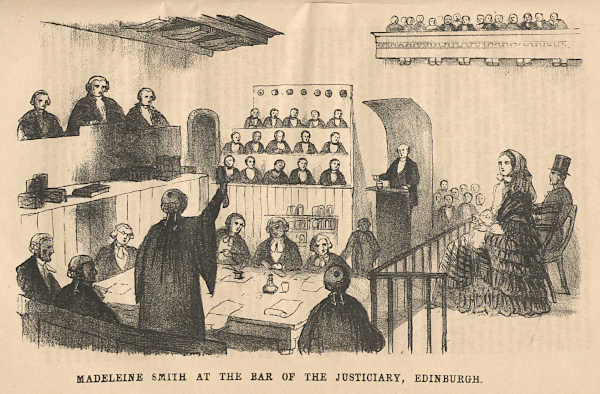

Her trial took place in Edinburgh, on the last day of June, and lasted just over a week. News reporters adored her; she was “ravishing”, with “bright eyes”, and took to the courtroom “like a belle entering a ballroom”. Every detail of her brown silk dress was commented on, as well as her lavender kid gloves, her white straw bonnet, and her black veil.

Of the three charges of murder made against her, one was found ‘not guilty’, and two were ‘not proven’. Madeleine was free to go, though without her name being cleared.

There was nothing ‘ordinary’ about any of this. And for all George Eliot’s declaration of Madeleine’s “least fascinating” aspect, her fellow novelists didn’t agree. Both Mary Elizabeth Braddon and Wilkie Collins drew on Madeleine as she was reported on in newspapers for their fictional portraits of the murderesses Lady Audley and Lydia Gwilt, in their ‘sensation’ novels Lady Audley’s Secret and Armadale.

The lack of clarity over the verdict continued to intrigue mystery and crime writers like Arthur Conan Doyle later in the century, and my own portrayal of Madeleine in my novel, Love and Other Poisons, is an attempt both to solve the crime and explore who Madeleine really was.

I’m not alone in that desire to understand an ‘ordinary Victorian murderess.’ Novelists have long found the 19th-century tally of women who kill a fertile ground for fiction. Between 1843 and 1892, seven of the most notorious women killers to be immortalised in fiction were brought to court: Grace Marks (1843), Martha Brown (1856), Madeleine Smith (1857), Constance Kent (1860), Florence Maybrick (1889), and Lizzie Borden (1892).

Of the seven — surprisingly perhaps, given that we are often told women don’t commit violent crime – only two used poison (Madeleine and Florence Maybrick, who was found guilty of poisoning her husband, John Maybrick).

Four used axes: Grace Marks was accused of involvement in a double murder that included a shooting and murder by axe and strangulation; Martha Brown stood trial for taking an axe to her abusive husband; Lizzie Borden was accused of bludgeoning her parents with an axe. Constance Kent, meanwhile, was found guilty of slashing her half-brother’s throat so hard she almost decapitated him.

All of these women were found guilty of the crimes of which they were accused, apart from Madeleine Smith (Not Proven) and Lizzie Borden (Acquitted). However, only one was executed: Martha Brown, who became the last woman in England to be publicly hanged. Her death was witnessed by Thomas Hardy, and it affected him so much that he never forgot it, basing his 1891 novel, Tess of the D’Urbervilles, on Brown’s case.

Elements of the Constance Kent case made their way into Wilkie Collins’s 1868 novel, The Moonstone, and possibly inspired Henry James’s portrayal of a woman who kills a child in The Other House (1896).

Echoes of Florence Maybrick appeared in Dorothy L Sayers’s 1930 novel, Strong Poison, and Grace Marks was the direct inspiration for Margaret Atwood’s 1996 novel, Alias Grace. Lizzie Borden fascinated Angela Carter, resulting in her 1981 novel, The Fall River Axe Murders, as well as Edith Wharton, who based her 1892 short story, Confession, on the tragedy.

In each case, the woman accused has known the person she is accused of killing. And while the methods have, in the main, been violent and extraordinary, the situations themselves have been domestic – the women have been accused of murdering a husband, a lover, an employer, a family member. Their victims are those with whom they live (or very nearly, in Madeleine’s case).

It’s not until the 20th century that fiction gives us a female serial killer; for example, in Daphne du Maurier’s Kiss me Again, Stranger or Joyce Carol Oates’s Starr Bright Will Be With You Soon.

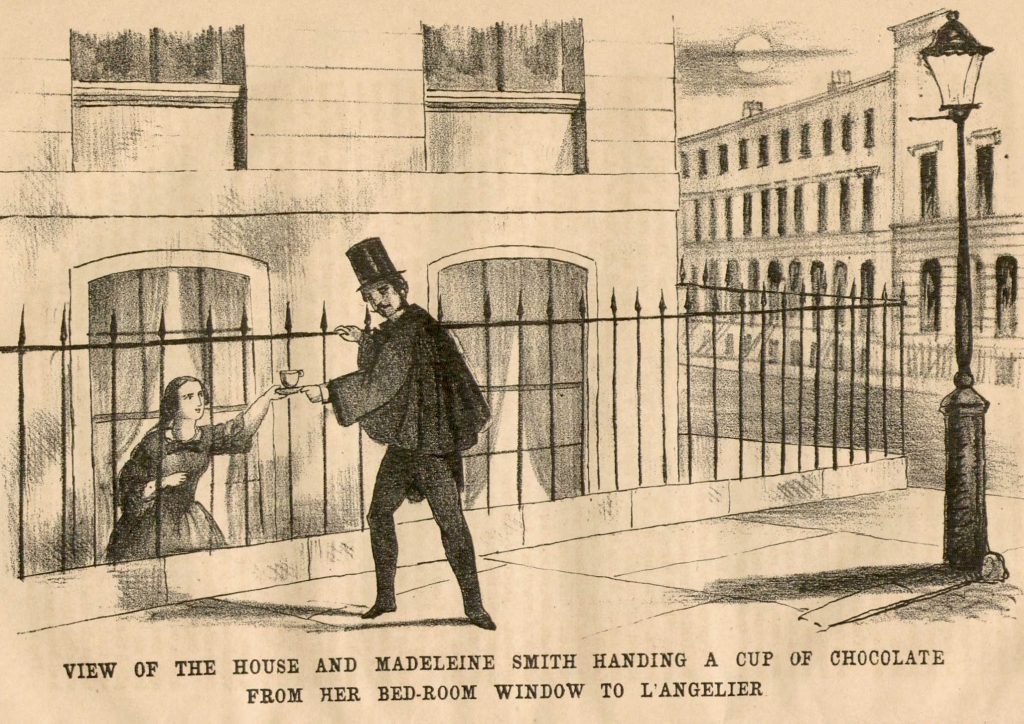

That domesticity was used by Victorians to ‘make polite’ a terrifying reality: with Madeleine Smith’s, cartoons of the time depicted a beautifully dressed young Victorian woman handing a top-hatted man a cup and saucer – meant to represent the means by which she had poisoned him.

But the cartoon shows Madeleine reaching from her Blythswood Square basement bedroom window up through the railings to her lover on the street, an impossible act, as the distance between the two is too great.

Even more mysteriously, the court case couldn’t explain how Madeleine managed to introduce so much poison into Emile’s body without his knowledge – over 200 grains of arsenic is hard to hide when it adheres to form a large lump in hot liquid. A cup of cocoa could never have been the means; but perhaps the real ‘how’ was just too shocking for Victorian society to contemplate.

Ironically, then, as a result of domesticating Victorian women’s true sexual voraciousness, or their propensity for violence, some guilty women survived the hangman’s noose, to be judged mad, or locked away to think about what they had done – or even, in Madeleine’s case, released.

And beyond that real-life freedom, one could argue that the Victorians’ need for ‘the ordinary’ in women made them even more extraordinary in fiction, too.

Love and Other Poisons by Lesley McDowell was published on 17 July, 2025.

Read more about Lesley’s book.

lesleymcdowellwriter.blogspot.com

You may be interested in Lesley’s other feature for Historia, Female sexuality in historical fiction.

Also relevant are:

Review: Alias Grace – the book, the woman and the miniseries by Anna Mazzola

Five infamous female poisoners by Elizabeth Fremantle

Giulia Tofana: poisoner, murderer, saviour? by Cathryn Kemp

Motives of a Bronze Age murderess by Susan C Wilson

Vampire or victim? The real Countess Báthory by Sonia Velton

Images:

- Madeleine Smith at her trial from Glasgow poisoning case: unabridged report of the evidence in this extraordinary trial, 1857: Wellcome Collection (public domain)

- Pierre Emile L’Angelier (supposedly) from Trial of Miss Madeleine H. Smith before the High Court of Justicary, Edinburgh, June 30th to July 9th, 1857, for the alleged poisoning of M. Pierre Emile L’Angelier at Glasgow, 1857: Wellcome Collection (public domain)

- Madeleine Smith at the Bar of the Judiciary, Edinburgh, from Full report, extracted from the “Times”, of the extraordinary and interesting trial of Miss Madeleine Smith, of Glasgow, on the charge of poisoning by arsenic of her late lover, Emile L’Angelier, including the correspondence, 1857: Wellcome Collection (public domain)

- Meeting of the Lovers in the Laundry from Full report, etc, see 3

- Constance Kent, c1860: Wikimedia (public domain)

- View of the House and Madeleine Smith Handing a Cup of Chocolate from her Bed-room Window to L’Angelier from Full report, etc, see 3