Joanna Plantagenet, Queen of Sicily, later Countess of Toulouse, was every bit as lionhearted as her more famous brother Richard I. As her biographer, Catherine Hanley, says, she “led an extraordinary life full of adventure and danger”, the more so because she was a woman. Joanna’s eventful life also illustrates many of the major issues of the 12th century. It’s time she was better known.

A child of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. A crowned monarch who travelled to far-flung realms, went on crusade, met kings and popes and exerted a great deal of political influence on twelfth-century Europe.

Not Richard the Lionheart, but his youngest sister, Joanna (also called Joan).

Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine are two of the most recognisable figures of the European Middle Ages, and almost certainly the best-known couple. The lives of their sons, particularly the kings Richard and John, have also been examined in detail many times, but the girls in the family have been rather overlooked.

This is not because any of them led a dull, humdrum existence: far from it. All three sisters travelled widely, and the youngest, Joanna, led a particularly extraordinary life full of adventure and danger (and not a little controversy) that was more than a match for those of any of her brothers, including the famed Lionheart himself.

Joanna’s life story is, in itself, a narrative of breathless, ceaseless action. She was born in Angers, in the heart of her father’s ancestral domains, in October, 1165, and spent her earliest years in the company of her mother and older sisters as they travelled between the family’s many domains in England and France.

Once her sisters were married Joanna and her younger brother, John, were sent to Fontevraud Abbey for their education, but this peaceful existence was not to last long as the warring family tore itself apart; when Eleanor of Aquitaine was imprisoned by Henry II, Joanna was removed from the abbey and sent to England to share her mother’s captivity.

At the age of 10 Joanna was obliged to make a prestigious international match chosen by her father, and she was sent hundreds of miles across the sea to marry the adult William II, king of Sicily. In this strange, new, hot and disorientatingly multicultural land the young Joanna dealt with an authoritative mother-in-law and endured the difficult lot of being a childless queen.

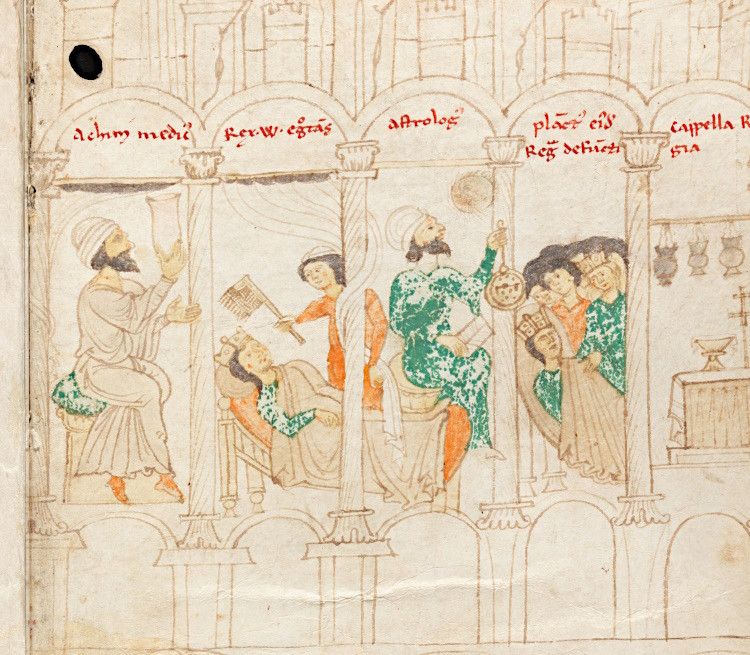

She was still only in her early 20s when William died – at which point, far from being treated with the respect due to a dowager queen, she had her lands and incomes confiscated and was captured and imprisoned by an illegitimate usurper.

After a violent interlude she was ‘rescued’ by her brother Richard, by now king of England, but when her rights and her money were restored Richard took it all for himself and his crusade expenses, meaning that Joanna was still left penniless and homeless.

Joanna accompanied her brother on his journey to the Third Crusade, now also chaperoning Richard’s fiancée, Berengaria of Navarre. The journey was an eventful one as the two women were shipwrecked off Cyprus and then attacked by troops in the service of the island’s devious lord. More violence ensued, resulting the conquest of Cyprus and Richard and Berengaria’s marriage there, before Joanna set off for the Holy Land once more.

She was an eyewitness to the bloody Siege of Acre of 1191 and its aftermath, moving into the palace there once the city fell to the crusaders and even as the bodies were still being cleared from the streets.

Later, Richard ordered the cold-blooded massacre of some 2,700 Muslim prisoners; Joanna was not party to this decision but an atrocity of that scale could hardly go unnoticed by anyone present and must have been deeply affecting.

She then became more personally involved in the peace negotiations when Richard thought it would be a good idea to offer her as a bride for al-Adil, the brother of the Muslim leader Saladin. Unfortunately for Richard, he had not thought to consult his sister about the arrangement; she was furious and, with the backing of various Christian churchmen, was adamant in her refusal.

When the time came to leave the Holy Land Joanna travelled with Berengaria in a separate ship from Richard’s. They made landfall in Italy but later found out that he had been captured and imprisoned by the Holy Roman Emperor. The women were obliged to take control of the situation and to make their own perilous way ‘home’ – wherever that might be – through Rome, Italy, Germany and France, all lands under the control of Richard’s enemies.

The short period of relative tranquillity that followed was ended when Joanna’s continuing value on the marriage market – as the king of England’s only available sister – came to the fore. In 1196 she was married to Raymond VI, count of Toulouse, with whose family the Angevins had been in dispute for decades.

Joanna was not the first, nor the last, woman to be used as a ‘peace offering’ in this way, and she attempted to make the best of it, living with Raymond and bearing him a son in 1197 and a daughter in 1198.

However, Joanna was not happy in the marriage, and she elected to do something that very few noble or royal women did: she left her husband. Pregnant with a third child, she fled the court of Toulouse and headed for Aquitaine, but she arrived only to find that Richard was dead. Joanna and her mother buried him; then, perhaps in remembrance of her peaceful childhood time there, Joanna asked to be admitted to Fontevraud Abbey as a nun.

This was an extremely unusual request for a woman who was both married and pregnant, and it shows the depth of her resolve not to return to her husband. Joanna’s request was accepted, but it was not long before she went into a difficult labour, during the course of which she died. Her child, a son, was born by post-mortem caesarean but followed her to the grave.

Joanna stands out from most other women of her era due to her extensive travels and her often daring actions.

However, her life is also a wonderful illustration of the wider issues of the time: royal child marriage and its implications for those involved; the international Plantagenet network and the disputes between territories and kingdoms; the multicultural milieu and religious melting-pot of Sicily and the Mediterranean; the Crusades and female participation in them; the social and political position of women, and how they could take independent action to build lives for themselves within the constraints that bound them.

Joanna represented, and was often the very personification of, many of these crucial issues. During her life she was variously a princess and a pioneer, a captive and a queen, a warrior and a wife, but she was never anything less than determined and independently minded.

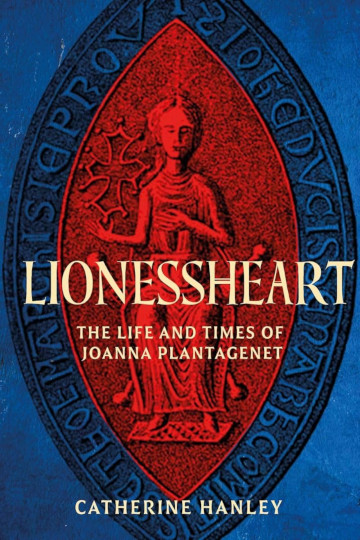

Lionessheart: The Life and Times of Joanna Plantagenet by Catherine Hanley is published on 20 March, 2025. It’s the first full-length biography of this extraordinary woman.

Read more about this book.

You may also enjoy these Historia features Catherine has written:

The personal and the political in the Middle Ages

Matilda: The greatest king England never had

England’s Forgotten King

More related features include:

Women and the Crusades by Carol McGrath

Female networks of power in the Middle Ages by JF Andrews

To have and to hold: pawns in the medieval marriage game by Anne O’Brien

Magna Carta’s inspirational women by Sharon Bennett Connolly

Images:

- Joanna and Richard I meeting Philip Augustus II of France (detail) from Histoire d’Outremer, 1232–61: British Library Yates Thompson MS 12, fol 188v via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Joanna, Countess of Toulouse, from the Genealogical roll of the kings of England: British Library, Royal 14 B VI, via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Joanna (the blonde figure wearing a crown) mourns the death of her first husband, King William II of Sicily [Bern, Burgerbibliothek, Cod. 120.II, f. 97r – Petrus de Ebulo: Liber ad honorem Augusti, lat (https://www.e-codices.ch/en/list/one/bbb/0120-2)]

- Richard and Berengaria from Li rommans de Godefroy de Buillon et de Salehadin by Maître de Fauvel: Bibliothèque nationale de France via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Seal of Raymond VI of Toulouse: Wikimedia (public domain)

- Fontevraud Abbey, the church: Matthias Holländer for Wikimedia (CC0 1.0)