2025 marks 80 years since the liberation of the Third Reich’s camps. This significant anniversary will likely be the last in which survivors are still alive to tell their stories. When writer Kate Thompson went to visit 95-year-old Renee Salt in her London home she had no idea of the journey of discovery it would take them both on.

I first met Renee Salt in October 2022 at the launch of an exhibition about Auschwitz-Birkenau in London. Renee, then 93, had come with the Holocaust Educational Trust to speak about her experiences. The silver-haired grandmother looked so small in front of the pack of photographers, and something in me folded. Surely this was too much for such an elderly woman?

Then she began to speak and I realised how clumsy I had been in my assumptions. Far from frail, she was the strongest, most resilient person in that room.

As a historical fiction and non-fiction author specialising in wartime women’s voices, I was surprised that her story had not already been told in a book. I visited her in her sheltered housing flat two weeks later, where I discovered her memories were undimmed by the passing years.

“If I want to say something about the past, I close my eyes and I see everything so clearly. It plays in my mind like a film,” she told me.

And what images to relive. Your 11-year-old sister being torn from your mother’s arms by the SS. The cattle trucks stuffed with human cargo. Arriving at Auschwitz-Birkenau and witnessing murder on an industrial scale. The ‘hills’ at Bergen-Belsen, which turned out to be corpses stacked one on top of another.

Renee has seen things no human should ever witness. Her experiences bear witness to some of the foulest atrocities of the past.

Renee’s book received multiple offers, but she and her family decided to sign with Seven Dials, an imprint of Orion.

There was no time to waste. With the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Third Reich camps looming, the book had to be ready for edits by the summer of 2024. Which left approximately six months to research and write a first draft.

As a journalist, the deadline wasn’t intimidating, but as the reality of the new book began to sink in, the subject matter was!

I have ghosted multiple memoirs and written a non-fiction on the contribution of working-class women to wartime society for Penguin called The Stepney Doorstep Society. But this book was about the Holocaust, an area I didn’t have any personal connection to or specialist knowledge.

“Whatever you do, don’t get it wrong,” a Holocaust educator warned as I began the research process.

The warning was scarcely needed. I became acutely and uncomfortably aware that there was no room for error.

Immediately, I began to meet with and interview experts in their field, including Holocaust educators, historians, faith leaders, tour guides and archivists, all of whom generously agreed to work with me to ensure accuracy and proof read the book.

I devoured every book on the subject I could and visited the archives, but nothing replaced visiting the sites of Renee’s persecution and retracing her footsteps.

In January 2024 I travelled to Poland and immersed myself in Renee’s story. I started in her home town and followed the train tracks that took her further into hell, from Zduńska Wola, north-east to Łódź, then south to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum.

I was travelling on comfortable trains, not crammed into freight wagons designed for cattle. I knew where Renee’s journey went and how her story would end up. This was not something she ever benefitted from.

It was in the Zduńska Wola ghetto that Renee’s childhood ended. Despite being only 11, Renee was put to work in a factory making socks for the Army. Starvation, disease and random executions were commonplace. But even these horrors paled into comparison when, in August 1942, the SS ordered parents in the ghetto to hand over all children up to the age of 18.

“Everywhere I looked, children were weeping, reaching out for their parents. Mothers were screaming,” Renee told me. “My mother tried to hide Stenia and me inside her coat, but it didn’t take very long before she was spotted. The Germans got hold of Stenia and my mother got a beating.

“My sister begged him to stop and then she ran away from us with tears running down her face. We never saw her again. Stenia, my brilliant and beloved 11-year-old sister was gone. We didn’t know where they were taking her, but we knew she wouldn’t return. It felt like my heart had been cut in half.”

The square where Stenia was taken, along with several hundred other children, is a very ordinary space. Youngsters bundled up in warm winter coats walked past me on their way to school. There was nothing to signal the abject horror of the morning so many children were stolen.

In the city of Łódź, it was poignant to find the records of the Berkowicz family, including the falsified date of birth Renee’s father gave to make her 16 instead of 13, which meant to the Germans she wasn’t a ‘useless mouth’ and could work.

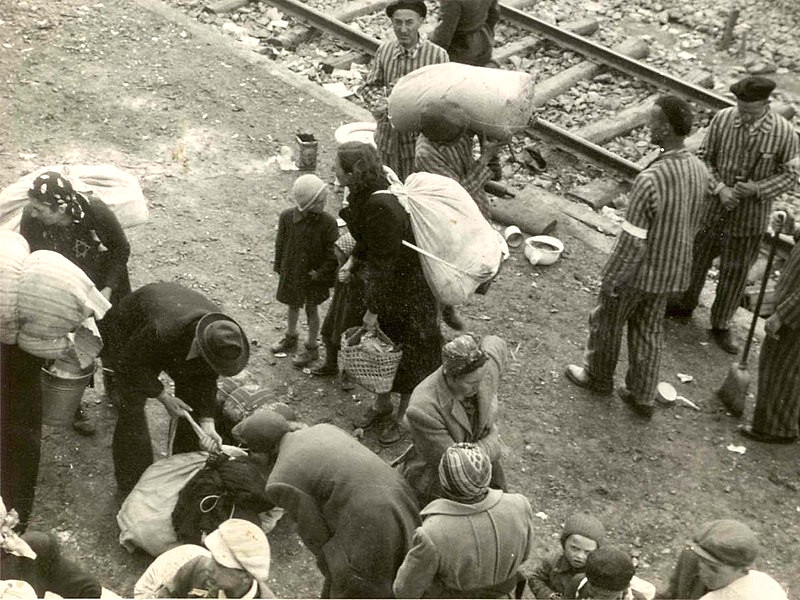

From Łódź, I travelled south to Auschwitz-Birkenau and stood next to the ramp where Renee and her parents were forced off the wagons into the hell of a smoky dawn in August 1944.

“An army of heavily armed Gestapo and SS men with lunging, barking, German Shepherd dogs were waiting on the platform shouting orders. It’s impossible to describe the chaos,” Renee told me about her arrival at the notorious death camp. “They shouted: ‘Raus! (Be quick.) Leave the luggage.’ My father jumped off first and I jumped after him. But by then he had disappeared into thin air, without a kiss or a goodbye.

“I never saw my father again. I believed he had died in the gas chambers. A terrible sickly-sweet foul smell filled the air and a thick noxious smoke hung over everything.”

I returned home and began to wrestle with the narrative structure of the book. How do you describe the indescribable? I decided that cold, hard facts work more effectively. Occasionally, the novelist sneaked in. Fortunately, someone whose opinion I trusted, had the sense to warn me, “you don’t want the tone or style to be a kind of Mills and Boon version of the Holocaust!”

Renee’s story never came in a linear way. It burst out, an unfiltered gush of history that at times threatened to overwhelm her. Every memory Renee recounted, I could see she was experiencing it physically, her fingers splaying out as if to grab at something, her eyes growing wide with fear.

Her trauma was a living thing. On many occasions, she would sit and weep, and I would hold her hand in silence, for what words of comfort could I possibly offer?

Soon after my return from Poland, came some shocking news. Eighty years on from Renee’s brutal separation from her father, Szaja, at Auschwitz-Birkenau, an International Tracing Report I had requested from the Wiener Holocaust Library in London landed in my inbox.

Szaja did not die in the gas chambers as Renee had always believed. He was transported out of Auschwitz-Birkenau on 1 September 1944 and sent to Kaufering IV, a sub camp of Dachau concentration camp, where he died on 20 January 1945.

Sitting down with Renee’s son Martin to share this news with Renee was a deeply emotional experience.

“It wasn’t easy to hear, but at least I know,” she told me. “After 80 years, my question has been answered. Knowing the date of my father’s death and what happened to him means I have closure.”

As a journalist, I am used to asking the questions, not answering them, but so much about this book was new, unchartered and raw.

My research ended at the site of Renee’s mother Sala’s grave, 400 miles north in the grounds of Bergen-Belsen, today a NATO training camp. Tragically, Sala survived to liberation, but died 12 days later on 27 April, 1945, weakened by starvation and injuries from an attack by a bull, which the SS had let out of a slaughterhouse in Hamburg for fun. She was 42.

When I got home to England, I finished the book and met the deadline. I wrote it faster than any other book I have written, the words tumbling out in anger at man’s inhumanity and awe at Renee’s courage.

Whenever I felt the weight of the story pressing down, I reminded myself that I may have travelled to the sites of Renee’s persecution, but only she had travelled deep into the abyss of human darkness.

It’s been the most challenging and visceral book I have ever written. The Holocaust defies the limits of language. What I have learnt is that stories are living, breathing things. In trusting me to tell her story, Renee handed me something alive, to be nurtured and cared for. And that is an extraordinary privilege.

On the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the camps, as the Holocaust moves from memory to history, memoirs like Renee’s become even more valuable. Telling Renee’s story at the age of 95 gives this book an unvarnished texture that travels to the heart of human existence.

Or, as New York Times bestselling author Natasha Lester remarked on reading it: “This is a story that proves to us that human beings are remarkable and endlessly inspiring.“

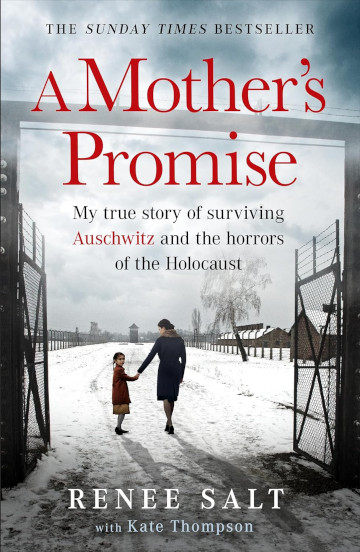

A Mother’s Promise: My true story of surviving Auschwitz and the horrors of the Holocaust by Kate Thompson and Renee Salt was published on 7 February, 2025.

See more about this book, which was an immediate Sunday Times bestseller.

Kate also makes the From the Library with Love podcast, in which she interviews Britain’s wartime generation — including Renee Salt. She’s written about her experiences in Why I started a podcast – and what I learnt.

Read about the extraordinary true stories behind her two most recent novels in Uncovering Jersey’s wartime resistance and Bethnal Green’s underground wartime library.

You may also be interested in these related features:

The voices of the Second World War by Ros Taylor

Writing popular history: Three lessons learned by Eric Lee

Three White Pebbles by Wendy Holden

Living in the minds of monsters by Douglas Jackson

Unseen Auschwitz by William Ryan

Auschwitz: the Biggest Black Market in Europe by Chris Petit

The Paradise Ghetto by Fergus O’Connell

Concentration camps and the politics of memory by Catherine Hokin

Images (all supplied by Kate Thompson unless otherwise specified):

- Charles, her British husband, and Renee Salt in 1949

- Kate interviewing Renee for her podcast

- Renee’s parents, Sala and Szaja Berkowitz, before the war

- Kate at Auschwitz-Birkenau in a barrack similar to the one Renee was imprisoned in

- Stenia, Renee’s sister

- People, including a mother and daughter, arriving on the ramp at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, summer 1944: Yad Vashem, the Auschwitz Album, via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Kate showing Renee (on her phone) the cemetery where her father, Szaja, is buried

- Women inmates queue for food, 17 April 1945, by Sgt H Oakes, No 5 Army Film and Photo Section, Army Film and Photographic Unit: IWM (BU 4013) (IWM Non Commercial Licence)