AD Bergin’s debut novel The Wicked of the Earth is set against the background of Newcastle’s 1650 witch trials. He talks to novelist and fellow North-Easterner Carolyn Kirby about the reasons behind witch hunts, the impact of the Interregnum on industry and society, and being a Northern author.

CK: Congratulations, Andrew! The Wicked of the Earth is a fascinating insight into a little-known corner of the English Civil War and a novel that really gets under your skin. I was so impressed with your grasp of the 1650s, a notoriously complex decade that could seem challenging as a setting for a debut novel. Did you have much prior knowledge about this period before embarking on your novel?

ADB: Thank you! No, this wasn’t my area of specialist knowledge before writing the novel. My PhD research was on the origins of the Duchy of Burgundy in the 9th century, so this book is a fair way from that! But my interest in the early modern period, especially in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, as the Civil War now tends to be known, grew stronger with age as I’ve come to realise how pivotal the conflict was for the emergence of the modern world, even as that world was slipping into something new and recognisably early modern. Today’s debates about class, exploitation and globalisation had their roots in the ideological ferment of the 1650s.

CK: I particularly loved the richly imagined picture of 17th-century Newcastle in your book. Newcastle’s built fabric from this time is largely lost, so what helped you bring the city so vividly to life?

ADB: There are one or two good historical texts and some excellent unpublished theses about the interregnum in the North-East, but mainstream academic historians don’t really get to grips with what was happening north of York.

However, the bones of Newcastle’s past; the castle, some of the steep alleyways or chares that rise up from the Quayside and St Andrew’s churchyard, all poke through into the present.

And fierce Geordie pride in the local area spans the centuries. We’re not Scotland, and we’re not quite England either. It’s a regional identity that springs from a sense of independence and a degree of cultural isolation in being remote from the capital.

CK: And I noticed the strangely enduring power of Newcastle’s great families, whose famous names crop up in your story.

ADB: Yes! Names like Blackett, Dobson and Fenwick are as evident in 17th-century records as they are on street names and businesses today. This longevity might be because the dominant coal trade was run for centuries by a cartel, known as the Hostmen’s Company, which stayed within the same families.

These dynasties were instrumental in the industrialisation of the city, not just coal-mining but ship-building and manufacturing. Tyneside in the 1650s was an early cradle of the developing modern world and I hope the book will speak not just to the history of the region but to a national audience as well.

CK: I thought I knew a reasonable amount about the early modern witch craze but I’d never heard of the Newcastle witch trial and it was actually England’s largest. Why do you think it’s not better known?

ADB: I really don’t know! I stumbled across an account of the Newcastle witch trial at the beginning of my research and was stunned. With 30 individuals prosecuted, the scale of this trial dwarfs that of the Pendle witches and witchfinder Matthew Hopkins’s proceedings in Essex, yet few people have heard of it. I thought, “How do I not know about this? How does everyone not know about this?”

And the Newcastle proceedings are also unusual because the victims seem to have come from relatively high-status families. Name after name of those executed for witchcraft are names also found on guild lists and even on the list of Hostmen. A Scottish ‘witch-pricker’ called Kincaid was paid extravagant sums to collect evidence by pricking the accused with bodkins. A flow of blood equalled innocence. But even contemporaries suspected that the evidence was fraudulent because the bodkins might be retractable.

Something fishy was going on in the Newcastle trial, and it was possibly connected to commerce and the coal-trade. A pamphlet by Ralph Gardiner, a merchant from Shields, is a rare primary source that hints at all of these strands. Reading it, I had the feeling that yes – this is the story I have to tell!

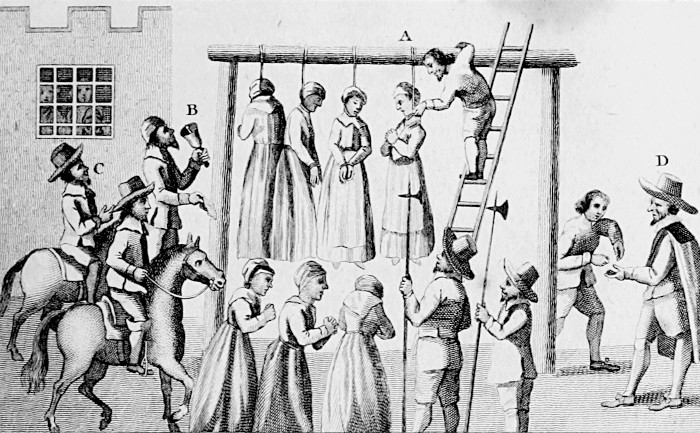

CK: All but one of the 15 victims who were hung on Newcastle’s Town Moor were women. If witch trials are viewed as a response to political and social turmoil, is there anything in Newcastle’s case that explains why this violent response was directed against women?

ADB: During the period of the wars, which lasted a full decade in the North, vast numbers of men were involved in the conflict and so women, of necessity, had extraordinary freedoms. They were left to manage farms and businesses, and the sources record that they largely did so with great success. Accusations of witchcraft were a uniquely effective method of silencing women, perhaps in an attempt to reassert traditional social and gender structures upturned in the years of conflict.

But in Newcastle, an all-female campaign led by Elinor Loumsdale to repeal the witchcraft accusations is a remarkable footnote to this episode. Although ultimately unsuccessful, the campaign’s survival in the records suggests how powerful the women’s protest must have been.

CK: Elinor Loumsdale is one of the historical characters in The Wicked of the Earth, but the story’s protagonist, James Archer is fictional. He is our moral compass through the story but he is also very much a man of his time. How did you put yourself in Archer’s shoes?

ADB: My very first thought for the novel was an image of a battle-scarred soldier trudging homeward up the Great North Road, full of longing but also dreading his return to Newcastle. Tasked with discovering the truth about the witch trial, Archer’s initial belief in the reality of witchcraft is sorely tested.

People thought and felt extraordinarily differently in Archer’s world. Your soul was always on the line and God was present in every disaster, so Archer is constantly reaching for scripture to put what he discovers into context. But the danger he faces in expressing dissent from mainstream beliefs has huge contemporary resonance.

Archer believes firmly in the Parliamentarian cause, but he is uneasy about the horrors he saw while fighting in Cromwell’s bloody Irish campaign. Archer’s central dilemma: how does one man remain good in a time of competing ideologies, results in a tortuous personal journey that feels very relevant to our own time.

CK: The Wicked of the Earth takes place in a specific point of recorded history but the story has a fictional plot and characters. Do you have any rules for blending fact and fiction?

ADB: As a trained historian, I can’t bring myself to change anything which is a historical fact. But the known facts of the Newcastle witch trial are relatively few. There are wrinkles and cracks in this evidence that point to the possibility that something more than superstition and religion was directing the course of the trial. Commercial interests could also have been at play, with lives being traded for economic benefits.

Hints and holes in the primary sources allowed me to weave my story into a coherent explanation of what might have really been going on, and who must have been involved. Yet I know I also need to create a gripping plot. So the novel has a classic crime story with a hunt for a murderer and a search for a missing sister. My aim is always to weave fact and fiction together in a way that respects both.

CK: That’s a great way to put it! And speaking of the facts of the story, I believe you’ve been instrumental in a campaign to commemorate the victims of the Newcastle witch trial in the city next year.

ADB: That’s right. 21 August, 2025, will be the 375th anniversary of the hangings on Newcastle Town Moor. A group of us, historical fiction authors, historians and heritage professionals, are campaigning to mark the occasion with a permanent memorial to the people who died.

But the Newcastle witch trial is only the tip of an iceberg. We know that Kincaid, the Scottish ‘witch-pricker’ was involved in witch trials across Northumberland and Durham as well as the Borders. There were probably hundreds of victims. Scotland already has memorials to those who perished in witch hunts there, and as Newcastle’s witch trial was the largest of the early modern period, its victims deserve to be remembered as well.

CK: Will we see more of James Archer?

ADB: I’m already working on the second book in this trilogy which will continue the story not just of James Archer but also some of the historical characters in The Wicked of the Earth.

Called Jerusalem Staggers, the second in the James Archer series will fill out my picture of the links between the interregnum, Newcastle’s industrial development, and the English colonial occupation of Scotland, showing how the 1650s really did lay the foundations of modern Britain. Book three will see James Archer involved with a Puritan sex cult. Yes, that was a real thing, and it came to a nasty end in the 1660s!

CK: Oh my! I can’t wait! Thank you so much, Andrew, for talking to me about your excellent book.

The Wicked Of The Earth by AD Bergin is published on 21 November, 2024.

Read more about this book.

AD Bergin was born in Northumberland and raised on Tyneside. He graduated from Cambridge University with a first-class degree in History, since when he has worked as an archaeologist, historian, researcher, postman, roofer, builder and barman.

Carolyn Kirby‘s debut novel, The Conviction of Cora Burns, was longlisted for the HWA Debut Crown Award in 2019. Her second novel, When We Fall, is a thriller and dark love story set between Britain and Poland during the second world war. Her third, Ravenglass, will be published in autumn 2025.

Images:

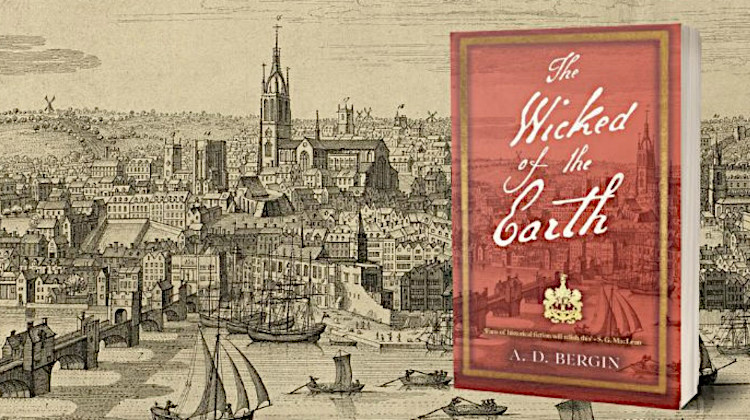

- The South-East Prospect of Newcastle upon Tyne by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck, 1745, with the cover of The Wicked Of The Earth superimposed: supplied by AD Bergin

- The Black Gate and Keep, Newcastle (site of the appalling torture engine used on the ‘witches’): R J McNaughton for Geograph (CC BY-SA 2.0)

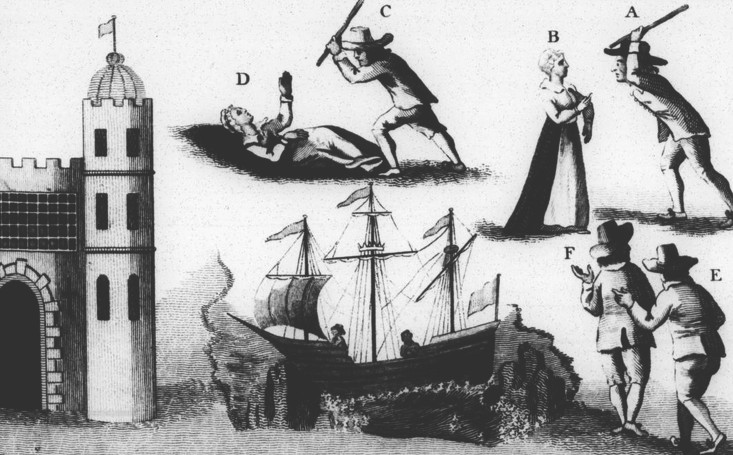

- Ann Cliff and Ann Wallice being beaten by Newcastle sergeants from England’s Grievance Discovered by Ralph Gardiner, 1655, reprinted 1796: Internet Archive (public domain)

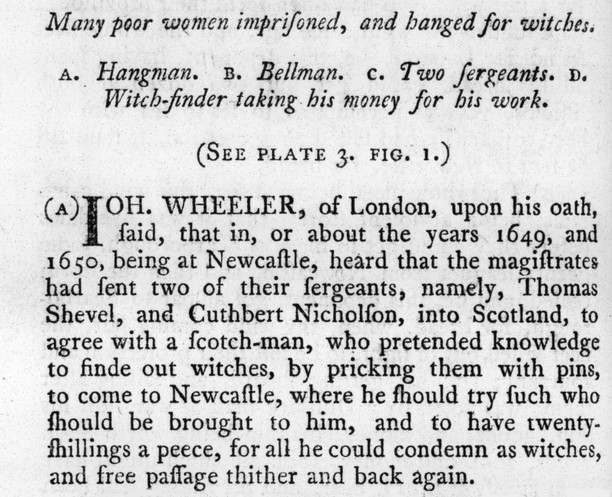

- Part of a page from England’s Grievance Discovered by Ralph Gardiner, 1655, reprinted 1796: Internet Archive (public domain)

- The ‘witches’ being hanged (see 4) from England’s Grievance Discovered by Ralph Gardiner, 1655, reprinted 1796: Internet Archive (public domain)

- The Guildhall on the Quayside, erected in place of the building where the Assize trial occurred: Andrew Curtis for Geograph (CC BY-SA 2.0)

- St Andrew’s churchyard, where the executed ‘witches’ were buried in a mass grave: Harry Mitchell for Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 3.0)