To put the coronation of Charles III in a historical context, I’m listing five coronations which are memorable for being the first, or the last, of their kind, or which took place in unusually difficult times. Some were also (unintentionally) amusing. And there are echoes, or perhaps foreshadowings, of the rituals followed in 2023.

Edgar: 1050 years of ceremony

Edgar (Eadgar) ‘the Peaceful’ or ‘Peaceable’ was born around 944 and became King of all England in 959. Though he was short, under five feet tall, and slim, he was handsome and strong, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. And his ambitions were large.

It may seem odd that his coronation, at Bath Abbey, wasn’t until 11 May, 973, almost 14 years after he took the throne. Historians re divided as to whether this was his first coronation or a second one held to mark the pinnacle of his kingly career.

What makes it doubly important is that it was this coronation ceremony on which all subsequent English coronations have been based; and it was the first known coronation of a queen consort of England – his wife, Ælfthryth. As she was his third wife, or at least the third partner to give him children, the crowning ceremony would give her son, Æthelred (remembered as ‘the Unready’) an advantage over his elder brother Edward (‘the Martyr’) – theoretically, anyway.

Edgar’s coronation ceremony was devised by St Dunstan, the Archbishop of Canterbury. We know details of the consecration because Dustan’s protege, Oswald, Archbishop of York, was also there and it’s described in Byrhtferth of Ramsay‘s Vita S Oswaldi. It tells us:

“Two bishops took the king’s hands and led him to the church, with everyone singing… ‘Let thy hand be strengthened and thy right hand exalted; justice and judgement are the preparation of thy throne; let mercy and truth go before thy face.’ When the antiphon was finished, they added, ‘Glory be to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Ghost.’ When… the king had prostrated himself before the altar, Dunstan… began to intone this hymn of praise [the Te Deum]… The bishops raised up the king from the ground… The king promised that he would keep three promises…

“When the service of consecration was complete, they anointed him and in exalted harmony chanted the antiphon, ‘And Sadoc the priest, and Nathan the prophet have anointed Solomon king in Gihon’, and drawing near him they said, ‘May the king live forever!’ After the anointing the archbishop gave him a ring; then he girded him with a sword; and after that he placed a crown on his head, and said a blessing; he handed to him both the sceptre and the rod…

“The king, crowned with laurel and decorated in roseate splendour, was, as I have said, sitting with bishops; with him also were all the handsome ealdormen and all the English nobility, gleaming attractively and rejoicing in the Heavenly King Who bestowed on them such a king… The queen, together with the abbots and abbesses, had a separate feast. Being dressed in linen garments and robed splendidly, adorned with a variety of precious stones and pearls, she loftily surpassed the other ladies present…”

While the actual putting on of the crown could be seen as the most important part of the event, it was the unction, the act of anointing him with consecrated oil, which was the most significant as it indicated that the monarch was chosen by God; the Lord’s anointed.

The fact that it was seen as a significant ceremony is underlined by the fact that texts A, B and C of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle break off their shorter narrative to commemorate it in verse.

It’s a pleasing coincidence that this year’s coronation is being held almost exactly 1,050 years after the ceremony was first used.

Richard II: the first procession

Richard II was 10 years old when he was crowned in Westminster Abbey on 16 July, 1377, just 11 days after the funeral of his grandfather, Edward III. It’s possible that the short timespan was influenced by fears that Richard’s uncle, John of Gaunt, might attempt some sort of coup; but the old King had been frail for some years and his death was not unexpected.

At any rate, the coronation ceremonies showed no sign of being thrown together in a hurry. Indeed, as the Proceedings at the King’s Coronation, a manuscript in the National Archives, shows, many people presented petitions claiming the right to carry out various offices (duties) during the proceedings. These included providing a glove for the King’s right hand and supporting the gloved hand while Richard held the royal sceptre; serving the King with a gold ewer and cup during the feast after the coronation; holding a hand towel for the King; and providing the royal kitchen with a cook to to make a pottage of almond milk, chopped chicken, sugar and spices for the banquet.

The day before the ceremony Richard processed from the Tower of London to the Palace of Westminster on horseback; in front of him rode the Earl Marshal, Henry Percy and the Steward, John of Gaunt, then Richard’s counsellor and former tutor Sir Simon Burley, holding the royal sword. This was the first ever coronation procession.

It had been 50 years since the last coronation, and interest was intense. Gaunt had to cut a path through crowds of onlookers and street entertainers. Houses along the way were bright with banners and tapestries. Wine flowed through the conduit at Cheapside, where the citizens had placed their own trumpeters, vying with the ones in the procession. It’s not surprising that the journey took about three hours.

Next morning Richard was dressed in white and it’s thought that he wore a pair of red slippers which had once belonged to St Edmund. The route to the Abbey was covered with scarlet cloth; an early red carpet? He walked with Gaunt, who carried the coronation sword, Curtana, beside him.

The ceremony, with Simon Sudbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury, officiating, is preserved in the Liber Regalis, still at Westminster Abbey, and follows the by-now familiar pattern. At its height, Richard’s shirt was removed behind a golden cloth. Holy oil was touched on his hands, chest, shoulders and head. Gaunt passed him Curtana, for the protection of the kingdom; he also had the sceptre, for correction of error. Then the Archbishop and the Earl of March placed the crown on his head. This was followed by the celebration of mass and homage from leading barons.

By now the 10-year-old King was exhausted. Simon Burley had to carry him on his shoulders to the banquet, and he lost one of his slippers on the way; this was later seen as a bad omen (or they might just have been too big for him).

There’s a contemporary portrait of Richard in his coronation robes sitting in the Coronation Chair in the Abbey. Dating from the 1390s, it’s the earliest known portrait of an English monarch.

James V: an infant king

On 21 September, 1513, the 17-month-old James V was crowned King of Scots in the chapel of Stirling Castle, 12 days after his father, James IV, was killed at the disastrous Battle of Flodden. He was the only legitimate son of the King to survive infancy.

His father had commented that his son “gives promise of living to succeed”, and the English ambassador wrote that he “is a right fair child, and a large of his age”. Still, this was a crisis; the government had to act quickly to secure the safety of the realm. James had to be crowned, and quickly. Fortunately for them, none of the adult male cousins in the line of succession made a claim to the throne and the powerful of the kingdom rallied to the little King and his young mother, Margaret Tudor.

Stirling, farther from the English army than Linlithgow or Edinburgh, was a safe choice, though no King of Scots had been crowned there before. The archbishop of Glasgow, James Beaton, was placed in charge of the hurried arrangements.

We don’t know much about the ceremony. Presumably the Honours of Scotland, the royal regalia, would have been used. They included a sword and sceptre given to James’s father by Pope Alexander VI as well as the crown; the child King would not have been able to hold or wear them, but perhaps he touched them symbolically. The ceremony in Scotland incorporated elements which reflected precedents in the Old Testament such as election, acclamation, enthronement and a pledge of allegiance along with crowning and unction.

The Lord Lyon, Sir William Cumming, would have entered the chapel first, then James – we don’t know who carried him – flanked by two bishops. The procession to the altar followed the crown, sceptre and sword; after James came the royal robe, seal and spurs. A sermon might have followed, the the two bishops anointed him on the “boughts of his armes, looffes of his hands, the toppes of his shoulder and ocksters” (elbows, palms, shoulders and armpits) as well as his head.

Then the Lord Lyon read out his ancestry from Robert II onwards, after which he would have been ‘crowned’. Somebody read out the royal oath on his behalf. Finally, and this may interest those who wonder about the oath UK citizens are ‘invited’ to take at this year’s coronation, the people of Scotland (through their representatives in the chapel) took the oath of fealty. The Lord Lyon read it aloud from the four corners of the coronation platform and the congregation agreed to it. Then Mass was said.

Two more points of interest: with so little time to prepare, music for the coronation may have been re-used from another event: it’s suggested that Robert Carver’s Missa Dum Sacrum Mysterium was chosen, though the late Kenneth Elliott believed that Carver wrote it for the event.

And the Honours of Scotland stayed in James’s mind. He remodelled the regalia later in his reign, and had a new crown made. We don’t know what his father’s looked like, but there’s an image in James IV’s book of hours which may show it.

However, despite the sterling efforts of the Archbishop of Glasgow and all the surviving Scots dignitaries, James V’s coronation is unsurprisingly remembered as the ‘mourning coronation’.

Charles II: an overlooked coronation

When we think of Charles II‘s coronation, we probably think of the one which took place on 23 April, 1661, the newly-restored King enthroned and resplendent in his robes or riding though the streets in a long procession. It’s often forgotten that he was first crowned 10 years before, on 1 January, 1651, at Scone in Scotland.

Just under two years before, his father, Charles I, had been executed; unconsulted about the trial and beheading of a King of Scots, and one from their ancient royal Stuart line, the Scottish Parliament almost immediately proclaimed the young prince King of Great Britain, France and Ireland at the Mercat Cross in Edinburgh. After negotiations, during which the new King had to agree to uphold the National Covenant, the Solemn League and Covenant, and the Presbyterian Kirk, he sailed for Scotland, arriving in June, 1650.

As the Scots began recruiting an army to support their new King, the English Commonwealth sent the New Model Army, led by Oliver Cromwell, across the border; at Dunbar, on 3 September, 1650, they defeated the Scots. Exactly a year later, Charles and the Scots lost the battle of Worcester and the King escaped into exile again.

This episode, and Charles’s coronation, are often seen as minor events in the history of the Interregnum. But scholars have recently argued that Charles’s Scottish coronation was neither hastily arranged on a shoestring, nor insignificant. In fact, it was lavish; it was revolutionary; and it was the last coronation to take place in Scotland.

Scone was chosen because the English army had taken Edinburgh and was likely to march on Stirling Castle next. More importantly, perhaps, Scone was where Scottish kings had been crowned for several centuries and was where the Stone of Destiny, their inauguration stone, had stood until taken to Westminster in 1296. This was a deliberate decision, not a compromise.

Research carried out by George Gross at Scone Palace has shown that there was considerable money spent on the coronation. It wasn’t overly splendid; that might not have been appropriate for a Presbyterian ceremony. Planning began in autumn 1650. Taking into account Charles’s stay at Scone during the first half of 1651, over £243,000 was spent on his household alone.

On the morning of 1 January, Charles, dressed in a ‘Prince’s robe’ of red velvet, processed from Scone Palace and up Moot Hill to the small church at the top, accompanied by Scottish nobles and the Honours of Scotland (including James V’s newer crown). There he sat under a canopy of red velvet. Beside him the regalia were placed on a table. Then all settled down for a sermon given by Robert Douglas, Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.

The sermon, covering 60 points, lasted for perhaps an hour and a half. I’ll spare you the details (it’s available online). Highlights included Biblical precedents for the coronation; the limitations of monarchy; how a (reluctantly) covenanted king should behave; and the sins of his father and his own sins (fairly gently, since Charles had already fasted to expiate those sins). No doubt to the great enjoyment of the new King.

After a prayer, Charles swore to uphold the Covenant, the Solemn League and Covenant and ‘Presbyterial Government’ and never to oppose them. After the Lord Lyon presented him to the congregation at each corner of the stage, asking them if they were willing to have him as their king (they were), Charles took the Coronation Oath and sat down “to repose himself a little” before taking off his red robe and putting on the royal robes, “the great mantle of purple velvet”. After he was invested with the sword and spurs from the royal regalia, he was crowned – not by a cleric but by the most powerful man in Scotland, the Marquis of Argyll.

I’ll skate over the rest of the ceremony, which included a recitation of Charles’s ancestors going back to the semi-mythical Fergus (to again establish his legitimacy as king?). many further exhortations from Robert Douglas, and the 20th Psalm.

All in all, the ceremony lasted about three hours, and the banquet that followed must have been welcome. Records show that “twenty-two salmon, a total of ten calves’ heads, vast numbers of partridges and meat” were bought, as were Bordeaux and Burgundy wines. Sugar confections and new embroidered linen napkins were made.

So far, so regal. But what was revolutionary? There was no anointing (it was superstitious), and Charles was crowned not by a member of the Church but by a nobleman. More strikingly, he was crowned King not only of Scotland, but England, Ireland and France, which was a remarkable extension of the Scots’ power and one which George Gross sees as “a shift from a Union of the Crowns, involving separate coronations, to an Anglo-Scottish union, but driven by Scottish aims”. Thirdly, it cemented Presbyterianism as the religion of Scotland. As Gross says, “the implications of this coronation were to bring the politics of the two countries even closer together, whilst the religious divide moved further apart.”

And finally, it was the last coronation to be held in Scotland.

George IV: Expensive and embarrassing

George IV‘s coronation on 19 July, 1821, was late. His father had died on 29 January, 1820, but the ceremony was postponed while a Bill designed to annul his marriage to Caroline of Brunswick went through Parliament. It failed; so he instead banned her from attending the ceremony in Westminster Abbey.

In the meantime, other bills had been mounting up. This was to be a hugely lavish and expensive coronation. A few figures: a total of £238,000 was spent, equivalent to around £27 million today, including preparation and furnishing Westminster Abbey and Westminster Hall (£16,819), jewels and plate (£111,810), uniforms, robes and costumes (£44,939), a new crown with over 12,000 diamonds (£50,000) and state diadem (£8,000), coronation robes (£24,000) and the banquet (£25,184). £100,000 of this came from government funds, with the balance made up from French war reparations.

George’s 27-foot red velvet robe was sold to Madame Tussaud’s but was bought back and has been used in every coronation since 1911. He wasn’t the only one to splurge on clothing, ruling that those attending the coronation should dress in Tudor- and Stuart-style costumes, with peers paying for their own outfits.

Meanwhile Caroline was making her own plans. At 6am on the morning of the coronation her carriage arrived at Westminster Hall. She was popular with the people and the waiting crowd applauded her; the soldiers and officials guarding the door became flustered and eventually shut the main door. She then got out of her carriage and approached the commander of the guard, saying that she was Queen didn’t need an entry ticket. When this didn’t work, she tried a side door; it was slammed in her face.

Accounts of what happened differ, but most agree that after further attempts she got back in her carriage and went to Westminster Abbey, where she was again turned away. Eventually, Caroline drove away to the accompaniment of crowds shouting “Shame! Shame!”. She fell ill the next day and died two weeks later.

The rest of the coronation ceremony at the Abbey seems to have taken place without too much further embarrassment. The only part of the ceremonies the general public was able to see was the 700-strong procession to Westminster Abbey.

There were large stands for spectators along the route between Westminster Hall and the Abbey; soldiers lined the raised, carpeted walkway. At the front of the procession the King’s Royal Herbstrewer and six maids walked, strewing their path with petals.

The procession returned to Westminster Hall in the mid-afternoon for the banquet. On the way another farcical event occurred; the Barons of the Cinque Ports had the right to carry a canopy over the King, but he chose to walk in front of the canopy. As the barons tried to catch him up, George, perhaps alarmed by the canopy’s swaying, walked more quickly, leading to “a somewhat unseemly jog trot” according to newspaper reports.

There were 1,268 diners at the banquet, seated at 47 tables (though there were so many that some had to be put in other parts of the palace). Many more sat watching it in specially-built galleries. What with the crowds, the July heat, and his heavy robes, George – notoriously overweight – sweated profusely, using up 19 handkerchiefs in mopping his face.

The ceremonial peak of the banquet was the arrival of the King’s Champion, in full armour, on his horse; his role was to challenge anyone who contested the new monarch’s entitlement to the throne to trial by combat by throwing down his gauntlet. Henry Dymoke, son of the hereditary holder of the position, had no horse of his own, so one was hired… from Astley’s Circus.

After George left, at about 8pm, the author Robert Huish writes that the spectators in the stands rushed down to eat the leftover food. Some also also tried to steal table decorations, plates and cutlery. Then, with the large number of people trying to leave at the same time, it took so long to get each carriage ready that that some the guests couldn’t leave Westminster until seven hours later.

That was the last time a coronation banquet was held, and the last time a King’s Champion issued a challenge. Perhaps not surprisingly.

Frances Owen is editor of Historia.

She’s written about a number of 17th-and 18th-century topics, including:

Good Boye or devil dog? Prince Rupert’s poodle

Remembering Culloden

Five surprising facts about Charles Edward Stuart

Richard II features in To have and to hold: pawns in the medieval marriage game by Anne O’Brien

Find out more about an older Charles II in The monarch with the magic touch by Andrew Taylor

George IV’s dressing up continues in George IV’s visit to Edinburgh in 1822 by Maggie Craig

Images:

- Richard II of England with his court after his coronation from the Chroniques d’Angleterre by Jean de Wavrin, 15th century: Wikimedia (public domain)

- Edgar with the Virgin Mary and St Peter, detail from the Winchester Charter: Wikimedia (public domain)

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicles A text showing the poem about Edgar’s coronation: Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 173: The Parker Chronicle

- Richard II in coronation robes: Wikimedia (public domain)

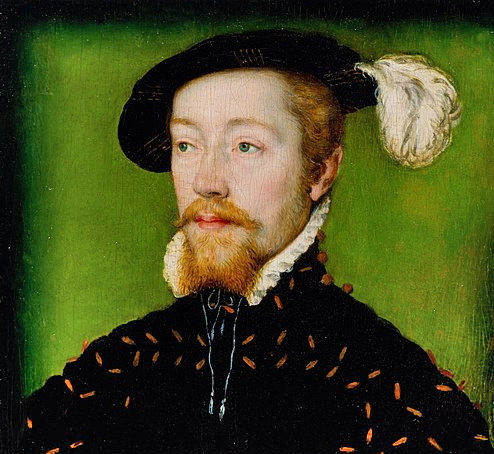

- James V by Corneille de Lyon, c1536: Wikimedia (public domain)

- Hours of James IV of Scotland (detail) by Gerard Horenbout: Austrian National Library via Wikimedia (public domain)

- The Coronation of Charles II as King of Scotland at Scone, 1 January 1651: Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

- Coronation of Charles II in Scotland, 1651: Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

- Coronation of George IV in Westminster Abbey after James Stephanoff: Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023 via Wikimedia

- George IV in his coronation robes by Thomas Lawrence, 1821: Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023 via Wikimedia