Katharine Quarmby’s investigation into the gruesome burial of a suicide victim — for felo de se — with links to her home town inspired her first novel, The Low Road. For Women’s History Month, she explains why this punishment fell disproportionately onto poor women, and what made her want to tell this story.

On a late spring evening in 1813 a ‘vast concourse’ of people from Harleston, my Norfolk home town, watched as the corpse of a young, unmarried mother, Mary Tyrell, was tipped into an unmarked grave at the end of the town and subjected to staking through the heart — an archaic practice known as felo de se.

Mary left behind her an orphan child, Ann, whose story I tell alongside that of her mother in my debut historical novel, The Low Road.

The story that became The Low Road caught my attention some seven years ago, when I was visiting my parents in the Waveney Valley, which runs between the border of the East Anglian counties of Norfolk and Suffolk.

Searching for a local walk I came across a reference to one Mary Tyrell, who had been buried on the parish boundary, between Harleston and Redenhall at a place known as Lush Bush in 1813. Something about this story just gripped me. I wanted to know why Mary had met such an awful end — and what had happened to her daughter.

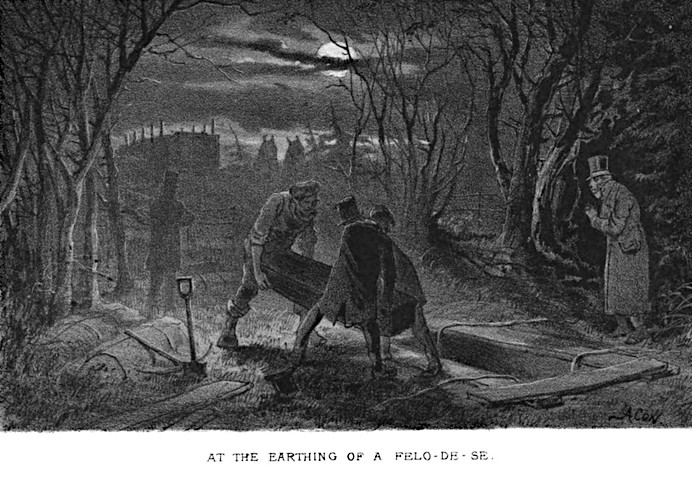

The inquest on Mary had recorded a verdict of felo de se (self-murder), as she was accused of infanticide before she took poison and died by suicide. As the regional newspaper, the Norfolk Chronicle, recorded at the time, after the verdict was passed on her dead body at the Swan Inn, the punishment was brutal: “on the same evening about seven o’clock she was buried in the high road with a stake driven through her body.”

In the Churchwardens Accounts by Charles Candler, published in 1896, he reported more details which he had obtained from an old man who had witnessed the burial when he was a very young boy.

“Creeping between the legs of the men who stood close round the grave, he saw in the gloom of the evening the parish constable fix the stake in position, while another drove it home with a heavy beetle, Mr. Oldershaw sitting his horse in silent charge of the proceedings”.

I imagined whether her daughter, Ann, called Hannah in my novel, had also witnessed this terrible scene, and so my research began. I found an analysis of such roadside burials in East Anglia, published in Folklore, by Robert Halliday, using local papers, which found 33 in the region over 59 years, between 1764 and 1823.

All of those buried were poor — servants and other working people. In six of them, including Mary, a stake was driven through the body — an additional punishment saved, it seemed, for those also accused of other crimes before they died by suicide.

One woman, Elizabeth James, who died just two years before Mary in Peterborough, after taking arsenic in despair, was buried by her relatives, all dressed in white. Other such roadside burials have often been thought to be Gypsies or Travellers, although whether this is true or not is debated.

Hidden East Anglia, which chronicles some of the forgotten stories of the region, has a list of some of the more gruesome roadside burials in East Anglia includes a ‘witch’ burial at a crossroads in the tiny hamlet of Howe Street, near Chelmsford, in Essex.

It is certainly no coincidence that East Anglia was the first region to experience some of the earliest witch hunts which followed the Civil War, as the local boy, Matthew Hopkins, scoured the region for ‘witches’ between 1645-1647, even coming to Mendham, close by my home town, and taking a woman from the parish who was later executed.

I write about his visit, and the oral memories that survived of the location for the ducking he did there, at Shotford Bridge, in The Low Road. “I was in the kitchen with the good wife, when she was dropping off one afternoon… she opened one eye, drowsy, and looked at me sleepily. ‘I remember my grandmama telling me that the witches were ducked there, and if they floated, they were condemned. Look around when we cross, my lovely, for if you see magpies, the witches will be nearby.’”

In 1823 the practice of felo de se was finally outlawed by Parliament. A year earlier, the foreign secretary, Viscount Castlereagh, had died by suicide; but his family was powerful and so his inquest, unlike that of Mary, passed a verdict of insanity. He was buried in Westminster Abbey — to what was reported as outrage at the time, as any poor person like Mary who had done likewise would have been buried on the public highway.

A Parliamentary debate in May of that year highlighted how the poor were far more likely to suffer this grisly punishment than the rich, with Mr Lennard, MP for Ipswich at the time, then introducing the Felo de Se Bill on 27 May, just six days later, calling it a “odious and disgusting ceremony”, which deprived the dead person “of the rites of burial”, and he called for the end of “the practice of running a stake through the heart, for he meant to leave the burial to be performed in private”.

I wonder whether Lennard had read some of the heartbreaking East Anglian cases of felo de se. After that, no families were put through the trauma of seeing their loved one staked in this way.

In The Low Road, it stays with Mary’s daughter, Ann, for years. These days, we might call this post-traumatic stress disorder, a haunting, if you will, of a child orphaned in the most awful way. When she recounts her story later, she says, “The worst comes first. If I could stand with the child I was, and take her by the hand, if I could pull that poor little girl to my breast so she could not see what is about to unfold I would, a thousand times.”

In my tranquil home town the story of Mary and Ann was forgotten for nearly 200 years. The place where Mary lies is a peaceful one, by a beck at the end of the town and, during lockdown, whenever I could visit my mother, we would walk down the town, past the inn where jury-men passed the verdict on Mary’s naked body, and then down the high street to Lush Bush.

She was a victim of circumstance, of being a poor woman who almost certainly was violated and wanted to conceal the birth of a baby she could not care for. She left behind a daughter who loved her and also disappeared from the history of my home town, when she was transported to Botany Bay 15 years after her mother died. I hope I have done their story justice in The Low Road.

The Low Road by Katharine Quarmby was released as an audiobook on 1 February, 2024. It was published in hardback on 22 June, 2023.

Read more about this book.

Katharine is an investigative journalist, editor and writer. The Low Road is her first novel.

Images:

- Fingerpost and trees near Lush Bush, Norfolk: author’s own photo

- At the Earthing of a Felo-de-se from The Wilds of London by James Greenwood, 1874: Google Books (public domain)

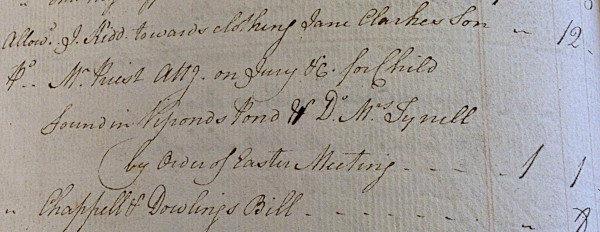

- Achive document about the baby found in the pond, from the Harleston records: author’s own photo

- The beck near Lush Bush where Mary Tyrell is buried: author’s own photo

- Trial and sentence of Ann Tyrell, 9 January, 1822: Old Bailey Proceedings Online version 9.0, Autumn 2023 (t18220109-20) (CC-BY-NC 4.0)