The ‘Horrid Popish Plot’, as it was called, was an anti-Catholic conspiracy that flared up in the 1670s; a classic example of fake news infecting the public imagination. Anna Abney examines the bizarre and sometimes shocking events.

‘Since Hell is broke loose, and the Press set a work,

By Jesuit, by Jew, by Christian, and Turk; …

Each Mome, and each Sot,

Now talks of the Plot,

Some cry it is true, and some swear it is not:

New Fire-balls in Pamphlets and Ballads are hurl’d,

To cajole the People, and amuse the World.’

(Anonymous broadside, 1679)

The Messenger of Measham Hall, the second book in the Measham Hall series, opens at the height of 17th-century England’s great conspiracy theory – that Jesuit priests, assisted by their gullible Catholic flock, were planning to assassinate Charles II and reintroduce Catholicism to England.

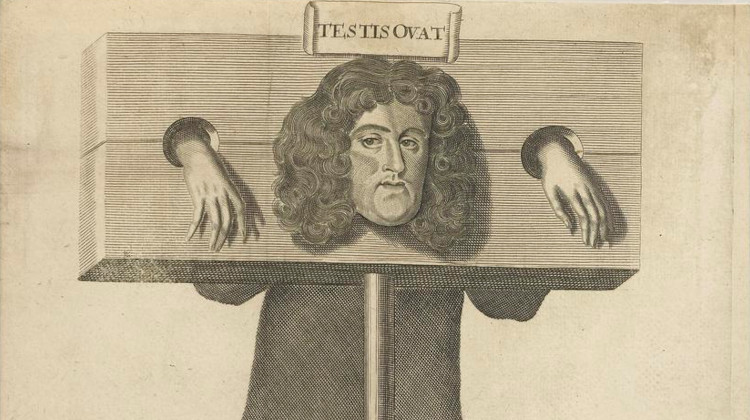

The ‘Horrid Popish Plot’ was in fact a fabrication by the larger-than-life Titus Oates, whose claims, backed by the fanatical cleric Israel Tonge, would result in the executions of at least twenty-two Catholics, while many more died in jail.

How did a man whose “testimony should not be taken against the life of a dog” (as John Evelyn later said of Oates) come to be considered the ‘saviour of England’? A man who had been expelled from every school and college he attended and had previously been found guilty of perjury.

Not only that, but Oates’ story was full of holes — he failed to recognise men he had implicated when taken to identify them, he frequently contradicted himself, and his claims were contested by numerous witnesses.

Despite his flimsy evidence, Oates, falsely using the title Doctor of Divinity and wearing Anglican vestments, managed to steamroller all before him with his absolute self-assurance. Whenever a contradiction in his evidence was pointed out he responded with yet more details and defences, sometimes blaming exhaustion or poor lighting for his lapses in memory and vision.

He was capable of holding forth for hours until he won over initially sceptical courtiers, judges and politicians, and crucially, it was this support from the authorities that leant weight to his fictional plot.

Oates was a consummate bluffer and his ability to stick to his story, no matter how absurd it appeared, proved irresistible to those only too willing to believe the worst of Catholics in general and Jesuits in particular.

“Never was a bear-baiting more rude and boisterous than this trial,” said an onlooker at one of the Old Bailey trials of priests accused by Oates (Kenyon, 1974, p184). Indeed, reading about the trials, even after several centuries, it is hard not to feel outraged by the injustices so obviously perpetrated.

It “will be very hard by way of Reasoning and discourse, to persuade the world that the age was so wicked as to act against their belief, or if they did believe it, that it was not true …” wrote Francis North, a judge at the Old Bailey, in his Instructions for a treatise to be wrote in undeceiving the people about the late popish plot.

In language that resonates today, North explained that “laying down facts” would not work, instead it would take some seriously persuasive rhetoric to overcome misinformation that had been so widely disseminated. (British Library: Manuscripts Add MS 32518-32520, spelling modernised; Peter Hinds, 2010, p85).

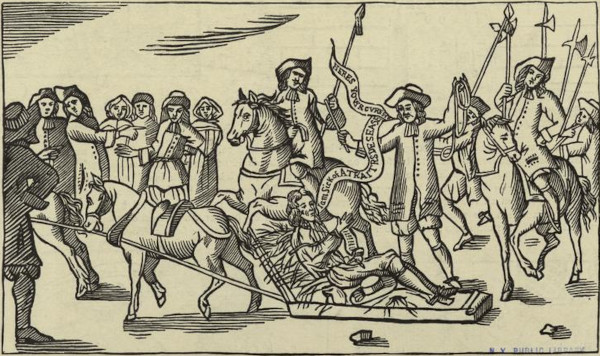

Encouraged by newsletters and pamphlets, England was gripped with terror of a Catholic uprising. Catholics were banned from within 20 miles of London and their weapons confiscated. All over the country Catholic ‘night riders’ intent on murder were heard on the roads, leading the House of Lords to debate whether papists’ horses as well as their arms should be seized.

Lists of suspected papists were drawn up and any who refused to sign the Oath of Allegiance were imprisoned. Oates allegations also led to the Exclusion Crisis — and the King’s Catholic brother James, Duke of York, was forced to move abroad for a while to escape the heat back home .

Restoration England was certainly ripe ground for spreading rumours about Catholic plots. Paranoia about ‘papists’ dominated the common consciousness. The Gunpowder Plot and the burning of Protestant martyrs under Queen Mary were still 17th-century reference points, as was the Great Fire of London, which was purportedly started by French Catholic fireballs.

Papists were distrusted because their allegiance was assumed to be to the foreign pope instead of the English king. Frequently described in terms of ‘vermin’ enslaved to a superstitious religion, their numbers were (wrongly) claimed to be rising, along with their influence. The poet Andrew Marvell promoted this view in his 1677 pamphlet An Account of the Growth of Popery and Arbitrary Government in England.

In addition to this, many Protestants were unhappy with Catholic influences at court; the Queen was a papist and so too was Charles’s likely heir, his brother James. Charles’s finances were dependent on loans from Louis XIV and anxieties about a French invasion were exploited by those who backed the plot.

In the contemporary war of words, one of those instrumental in discrediting the Popish Plot was the journalist Sir Roger L’Estrange (nicknamed Clackfart by his opponents), who fearlessly exposed the flaws in Oates’s (and his allies’) accounts in his periodical The Observator.

Allowing the publication of the accused priests’ final speeches also backfired by inspiring admiration instead of the intended derision.

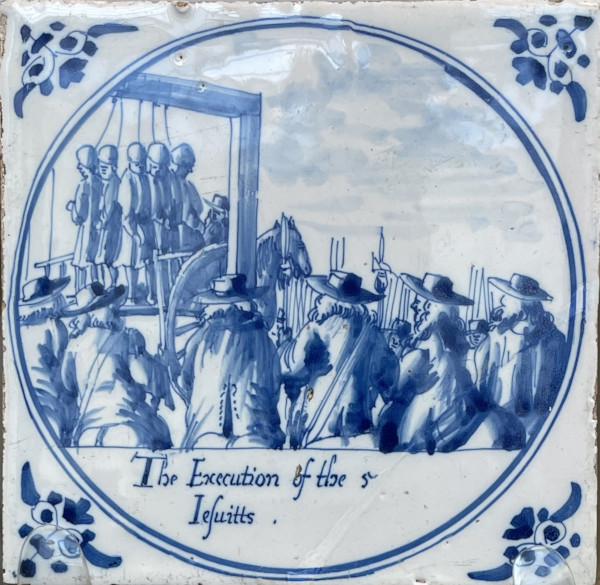

Kenyon suggests that the consistent denials of those convicted started to tug at the public conscience. Crowds at the executions began to stand in silence listening to the final words of those about to be hung and were even said to be reduced to tears by some of them.

Oates would eventually face trial himself on two counts of perjury and there would be some soul-searching, as well as convenient amnesia, on the part of those involved in the prosecutions of the ‘plotters’.

Summing up at Oates’s trial, Judge Jeffreys declared: “our nation was too long besotted, and of innocent blood there has been too much spilt… let us have a care for the future that we be not so suddenly imposed upon by such prejudices and jealousies as we have reason to fear such villains have too much filled our heads with of late” (Kenyon, 1974, p.293).

In our current era, rife as it is with ‘fake news’ and conspiracy theories, as well as those only too eager to fill our heads with prejudices, we might do well to heed his advice.

The Messenger of Measham Hall by Anna Abney is published on 29 June, 2023.

Read more about this book.

Anna Abney is a novelist and academic who also writes under the name Madeline Dewhurst. She is currently writing the third book in the 17th-century Measham Hall series.

Have a look at Plague and pandemic: how we responded then and now, the feature she wrote about the inspiration for The Master of Measham Hall, the first book in the series.

For more on the later 17th century, these other features might interest you:

The monarch with the magic touch by Andrew Taylor

Catherine of Braganza, the neglected Queen by Linda Porter

Charles II’s last mistress by Linda Porter

Aphra Behn: A Secret Life by Janet Todd

And so to bed – a goodbye to Pepys’s diary by Deborah Swift

Thomas Blood and the Theft of the Crown Jewels by Angus Donald

Why the Glorious Revolution was . . . well, neither by Angus Donald

The Battle of Killiecrankie by Maggie Craig

Charles II’s Scottish coronation features in Five memorable coronations by Frances Owen

HWA Crowns winners interviews: Andrew Taylor by Poppy Evans

And there’s more 17th-century fake news in Good Boye or devil dog? Prince Rupert’s poodle by Frances Owen.

Further reading:

‘The Horrid Popish Plot’: Roger L’Estrange and the Circulation of Political Discourse in Late Seventeenth-Century London by Peter Hinds, 2010

The Popish Plot by John Kenyon, 1974

Hoax: The Popish Plot that Never Was by Victor Stater, 2022

Images:

- A broadside on Titus Oates, referring to his false evidence of the Popish Plot, with an engraving showing Oates standing in the pillory (detail). (Testis ovat is an anagram of his name and means ‘the witness enjoys, exults’), 1685: © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- Charles II by Peter Lely, c1670: Royal Museums Greenwich BHC2609 via Wikimedia (public domain)

- The Execution of the 5 Iesuits, tile: © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- Edward Coleman drawn on the Hurdle to Execution, 1678 (Coleman was secretary to the Duchess of York): New York Public Library b17252184 (public domain)

- Titus Oates by Godfrey Kneller: Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge GC0017 via Wikimedia (public domain)

- The Doctor Degraded; or the Reward of Deceit (Oates in the pillory), 1685: © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)