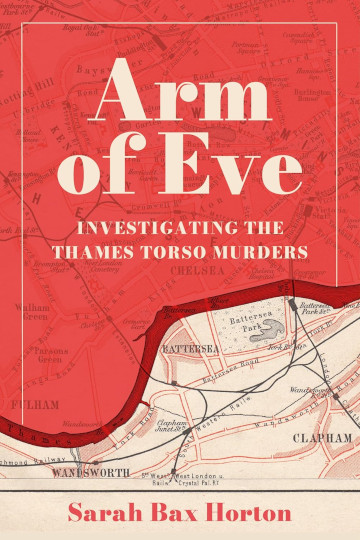

When Sarah Bax Horton discovered a police ancestor who worked on the Jack the Ripper investigation, her research led her to write two non-fiction books based on the Metropolitan Police Whitechapel Murders files. Her second book, Arm of Eve, proposes a new prime suspect for the Thames Torso Killer, a serial killer active at the same time as the Ripper in the nation’s capital.

Microfilms of the Metropolitan Police Whitechapel Murders files are available in the open access room of the National Archives at Kew. Although permission is required to view the original files and photographs, anyone can load up the reels and read through the police reports and contemporaneous press clippings that constitute the Ripper files.

While much has been lost, blitzed, pilfered and weeded out in the intervening years since 1888, that sparse, haphazard collection of papers still makes a fascinating read.

While researching my first book One-Armed Jack: Uncovering the Real Jack the Ripper, written in honour of my great-great grandfather, police sergeant Harry Garrett, I realised that Jack the Ripper was not the only serial killer under active investigation by Scotland Yard detectives at that time.

In the summer of 1888, the Press declared “an epidemic of murder” in an outbreak of crimes not limited to those committed by the Ripper and his lesser-known counterpart the Thames Torso Killer.

The Torso Killer has always lurked in the Ripper’s shadow, despite the fact he murdered and dismembered at least four women over two years in an overlapping period of time. He started to kill in April 1887, over a year before the Ripper, and his last murder was in September 1889, almost ten months after the death of Mary Jane Kelly, the Ripper’s last victim.

The Torso Killer deposited his victims’ body parts at diverse locations including the tidal River Thames. His crimes were named after the places where the torsos or first body parts were found: Rainham in Essex, Whitehall, Battersea and Pinchin Street in Whitechapel.

The police were unable to place the Torso Killer in any specific area of London, a difficulty which was aggravated by the non-identification of all but one of his victims.

Unlike Jack the Ripper, who was a silent and terrifying marauder on the streets of Whitechapel, the Torso Killer posed a threat that might be termed ‘non-specific.’

His murders were equally grisly and horrific, targeting vulnerable victims that included a pregnant woman and her unborn child, yet their perpetrator did not form a lightning rod for the nation’s fear.

A key document for any researcher into the Thames Torso Murders is a report in two parts written by Dr Charles Hebbert. The report was compiled from lecture notes for students of forensic science. In it, Hebbert demonstrated how the post-mortem examination of a murder victim could assist in identifying the body, where possible state the cause of death, and deduce characteristics about the victim and perpetrator to direct the police investigation.

The Hebbert report definitively unites the four crimes committed in the period 1887–89: “The mode of dismemberment and mutilation was in all similar, and showed very considerable skill in execution, and it is a fair presumption from the facts, that the same man committed all the four murders.”1

It makes two vitally important points, the first in the manner of Sherlock Holmes observing “the golden rule… that a medical man, when he sees a dead body, should notice everything”.

And the second, that, chillingly, “the cases taken as a whole are valuable as illustrating the difficulties we labour under in describing a person from such imperfect data, and as showing how a skilful, determined individual can murder and dispose of four bodies without detection.”

Whilst researching my duology, I noted the interplay between the two separate series of unsolved crimes. Scotland Yard firmly stated that the four Torso murders were by the same hand. Yet certain coincidences of timing and location were uncanny.

The second Torso murder of August 1888 occurred as the authorities and public realised that the Whitechapel Murderer, later nicknamed Jack the Ripper, was two or three murders into his killing spree.

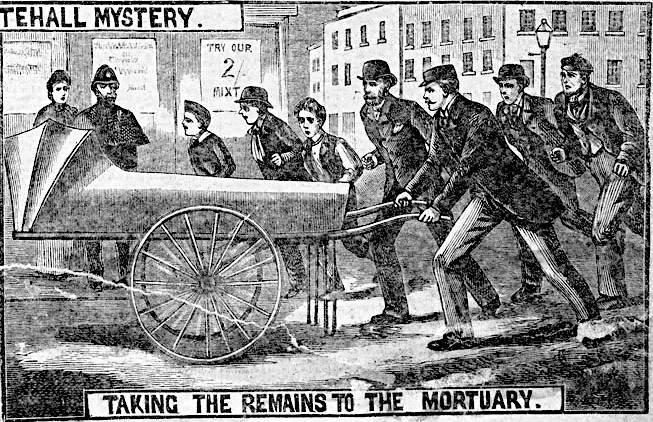

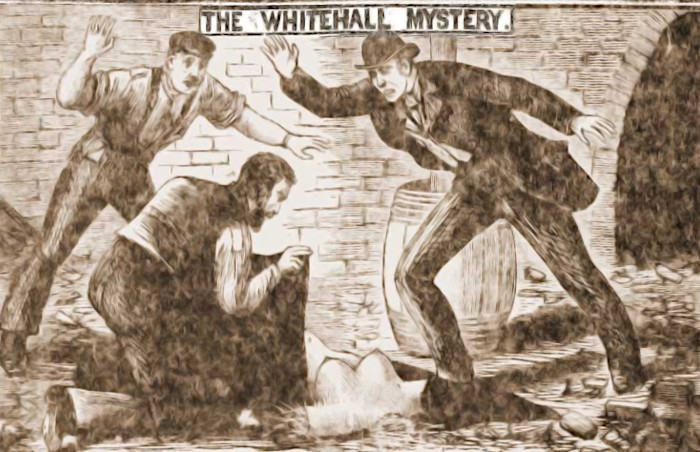

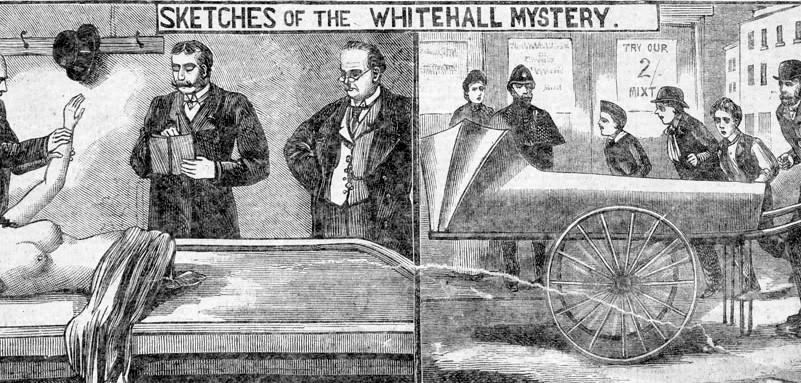

Extraordinarily, the Whitehall Mystery‘s body parts were deposited in the building foundations of New Scotland Yard while under construction on Victoria Embankment.

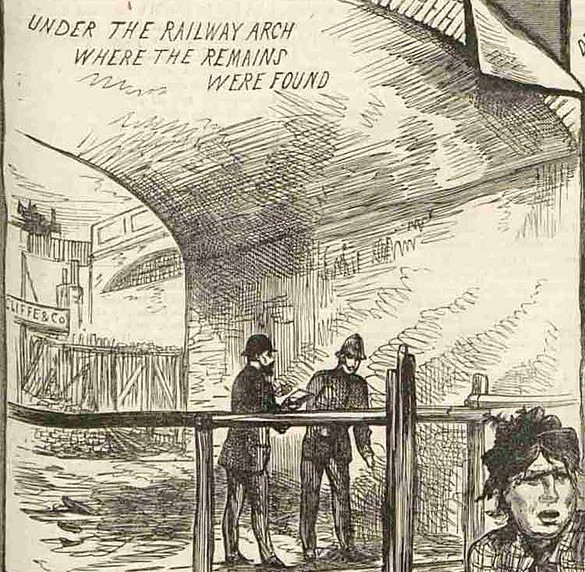

In September 1889, the so-called Pinchin Street torso case, was commonly attributed to Jack the Ripper despite its perpetrator being the also-unidentified Torso Killer.

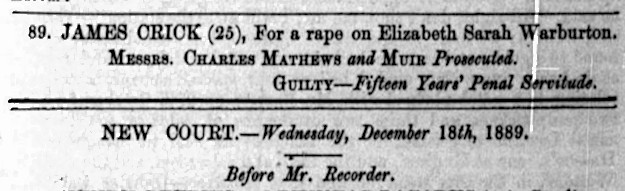

It occurred at a time when my prime suspect as the Torso Killer, waterman James Crick, was on bail for the rape and attempted murder of a female stranger.

Its location was within a couple of minutes’ walk of the Ripper murder location of Berner Street (today’s Henriques Street) and the headquarters of the Ripper investigation, Leman Street Police Station. In my hypothesis, although Crick evaded being charged with multiple murders, he was convicted of a serious lesser offence, for which he was sentenced at the Old Bailey to 15 years’ imprisonment with hard labour.

A previously undiscovered suspect as the Torso Killer, Crick is arguably the best yet. And, 135 years later, it is likely that no better will be found. He was a violent sex offender who was mobile on the capital’s waterways, meaning that he could access the diverse locations which feature in the case. The inland sites for depositing body parts all have close access from the river or docks.

I piece together a case against him, ending with a true crime reconstruction of each murder. If not Crick, the Torso Killer was a man very like him; highly mobile and skilled, a river worker based on the south bank and operating in central London.

I conclude by asking two questions: Was James Crick the Thames Torso Killer, or a violent rapist who paid his debt to society? And, if Arm of Eve argues a sufficiently convincing hypothesis, to what extent was justice done in his lifetime?

Arm of Eve: Investigating the Thames Torso Murders by Sarah Bax Horton is published on 31 October, 2024.

One-Armed Jack: Uncovering the Real Jack the Ripper was published on 31 August, 2023.

Sarah Bax Horton is a former civil servant and management consultant. She has an MA Joint Honours degree in English and Modern Languages (German) from Somerville College, University of Oxford. An expert on the Whitechapel Murders and an experienced genealogist, her genres are true crime and historical biography.

You may also be interested in Matthew Plampin‘s interview with Hallie Rubenhold, author of The Five.

Other related features include:

Dr Kahn and the Victorians’ fascination with anatomy by Essie Fox

‘Paedo Hunter Turns Prey!’ The ironic fate of the father of tabloid journalism by Carolyn Kirby

Images:

- The London Murder-scare from the Illustrated Police News, 3 November, 1888: Wikimedia (public domain)

- Sketches of the Whitehall Mystery from the Illustrated Police News, 20 October, 1888: Wikimedia (public domain)

- The Whitehall Mystery from the Illustrated Police News, October, 1888: Wikimedia (public domain)

- Sketches of the Whitehall Mystery: see 2

- Under the Railway Arch where the Remains were Found from the Penny Illustrated Paper, 21 September, 1889: Wikimedia (public domain)

- James Crick sentence, 15 December, 1889: The Proceedings of the Old Bailey (fair use)

1 Sources for the two-part Hebbert report are:

Ed WH Allchin, MBLond, FRCP, George Cowell, FRCS, and CA Hebbert, MRCP, The Westminster Hospital Reports, Volume IV ( J & A Churchill, 1888), ch VI

Charles A Hebbert, MRCP, An Exercise in Forensic Medicine

Ed Octavius Sturges, MDCantab, FRCP, and George Cowell, FRCS, The Westminster Hospital Reports, Volume V ( J & A Churchill, 1889), ch XI

Charles A Hebbert, MRCP, An Exercise in Forensic Medicine, Part II