Rudyard Kipling famously wrote about Calcutta, and not to praise it, says Vaseem Khan, author of the Malabar House crime series. He looks at the history of the first capital of British India, its place in the independence movement, and why men like Kipling despised both it and the Bengalis who used the written word to move the revolution forward.

Calcutta – now Kolkata – is not an ancient city.

The capital of Bengal, the city began life on the banks of the Hooghly River, entering the historical record in 1690 with the arrival of the British East India Company. By 1712, the British had ennobled the city with a fort – Fort William, later the site of the infamous ‘Black Hole of Calcutta’.

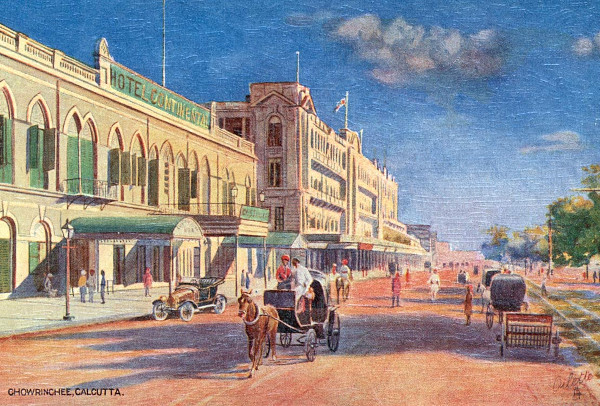

In Death of a Lesser God, the fourth book in my Malabar House series, the second half of which is set in 1950s Calcutta, I describe the city thus: “Once a pestilential riverine swamp, infested by bamboo jungles where tigers roamed freely, snacking on unsuspecting locals, the city was, in part, an invention of the British, who’d purchased the rights to the local land and the villages that sat upon it. One of those villages had been Kalikata, from which it was said Calcutta took its name.”

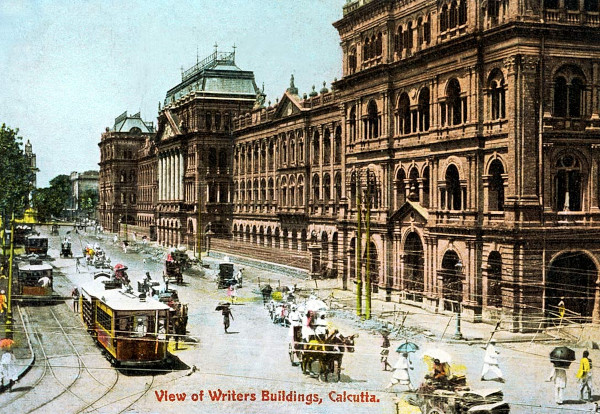

Calcutta became a base for British operations in India, with the colossal Writers’ Building housing the monolithic bureaucracy needed to govern the subcontinent – ‘writers’ being the name for the army of East India Company clerks who populated the building, dressed in woollen suits in the searing tropical heat, mildewing in the annual monsoon, and dying, variously of dysentery, malaria, and drunkenness.

Over time, the city became mired in the independence movement, until, in 1911, fed up with the argumentative Bengalis, the British upped sticks and moved their base of operations to Delhi.

As the glory of empire, and its ostensible civilising mission, faded; as war arrived, bringing with it economic hardship and immigration, the city too suffered. I continue in Death of a Lesser God: “In recent years, Calcutta’s population had swollen. Refugees from Burma, following the Japanese World War Two campaign there, and, later, during the Partition years, from the eastern half of Bengal… If Bombay was said to be the city of dreams, then Calcutta was where dreams came to grief against the shoals of political reality.”

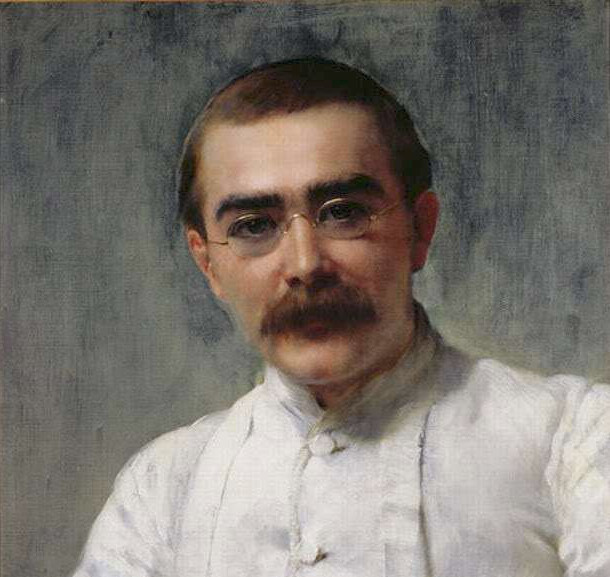

Rudyard Kipling, revered stalwart of the British literary establishment, and lifelong cheerleader for empire, famously wrote about Calcutta, and not to praise it.

Kipling was born in Bombay, in 1865. Following a childhood spent in England, he returned to India and began work as a journalist, eventually finding himself at the Pioneer, an English language newspaper that, till date, remains the second oldest in India (after The Times of India).

In 1888, Kipling visited Calcutta. His thoughts on the city and its inhabitants would later find expression in a series of polemical articles collected under the title The City of Dreadful Night and Other Places. Kipling, though at times willing to award the city faint praise, was openly critical of both its physical aspects and what he considered its ruinous civic administration, resulting in economic and political anarchy.

His views were coloured by his deep-seated belief that natives were eminently unqualified to run their own affairs. (Later, Indian politician Shashi Tharoor, would comment drily: “Kipling, that flatulent voice of Victorian imperialism, would wax eloquent on the noble duty to bring law to those without it.”)

Kipling depicts Calcutta as a city of abominable smells, unsightly poverty, and incorrigible disorder, placing himself in the role of a modern Dante, journeying through one Inferno-like circle of hell after another. Kipling reserved his most ardent ire for the Indians he deemed responsible for this state of affairs: the rabble rousers bleating for self-rule.

He hated the idea of the independent-minded Indian. In Calcutta, Kipling found the Bengali liberal elite intolerable, men – and a handful of women – who not only did not know their place, but were actively seeking to supplant the ‘natural order’.

Subversiveness had long been second nature to the Bengalis, who, with the exception of India’s guerrilla revolutionary, Subhash Chandra Bose, were not as keen as their Punjabi cousins to fling grenades into government buildings, relying instead on their skills of debate, their flair for written rhetoric, and a canny grasp of legal minutiae to harangue their British overlords.

I describe them thus, with my tongue firmly in my cheek, in Death of a Lesser God: “The problem with Calcutta, he’d explained, was that it was full of Bengalis – or rather, the sort of Bengalis who were so supremely in love with themselves that they’d convinced anyone who would listen that they and they alone were the torchbearers of art and literacy on the subcontinent, the doyennes of culture, poetry, political rhetoric, and fish…

“He’d always maintained a soft spot for the irascible Bengalis, with their love of disputation and their lofty ideals; he admired, too, their adoration of the written word, for which they’d gladly have given their lives, had they not been so averse to the sight of blood.”

And yet, despite his obvious superiority complex, Kipling’s fiction depicted an India where his fascination – and occasional admiration – for its exotic charms was also evident. This dualistic outlook was shared by many Indians, who, while seeking to supplant their colonial masters, often bore them little ill will. Indeed, Gandhi’s non-violent independence movement could not have succeeded had this not been the case.

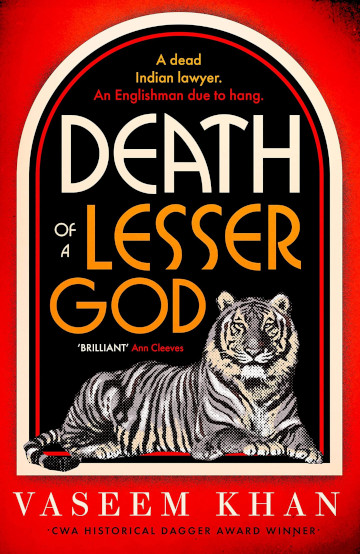

This dichotomous attitude lies at the heart of Death of a Lesser God, which asks a simple question – can post-colonial societies treat their former colonisers justly?

James Whitby is an Englishman born in India during the Raj, convicted in post-Independence India of murdering a prominent Indian lawyer. He claims he is innocent, the victim of a form of ‘reverse racism’.

My protagonists, Inspector Persis Wadia, India’s first female police detective, and Archie Blackfinch, an English forensic scientist working in India, have 11 days to find out if Whitby is innocent or guilty before he is hanged. The clock is ticking!

The novel begins in Bombay, before the action moves to Calcutta, where a cold case might be linked to Whitby’s alleged crime – the case is that of the murder of an African-American soldier just after the war.

If the idea of Indians acting as if they owned the place in their own country caused Kipling consternation, his head might well have exploded at the sight of some 20,000 African American GIs on the streets of Calcutta during the Second World War, crowding out the local bars, haggling in the brothels, and expressing themselves freely with the locals – who had never encountered black men before.

Today, Kipling remains a divisive figure. It has been alleged that he was not only an Indian-hater, but also a supporter of Brigadier-General Dyer, the man behind one of the most infamous incidents of the Raj, the massacre of hundreds of unarmed men, women and children in the walled garden of Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar in the Punjab in 1919.

On the other hand, many Indians revere him as a towering figure of literature. India’s first Prime Minister, Nehru, cited Kim as one of his favourite novels, and adaptations of Kipling’s work, such as Disney’s recent billion-dollar-grossing The Jungle Book, continue to find audiences.

The Malabar House novels, beginning with Midnight at Malabar House, were born of my desire to explore India just after Independence, a nation still reeling in the wake of Gandhi’s assassination and the horrors of Partition when a million Indians died in communal riots.

My lead character, Persis, is determined to prove herself in a man’s world, but is banished to Bombay’s smallest police station, Malabar House, populated by rejects and misfits. (The Times said: “Think Mick Herron in Bombay.”) The books contain many characters that reflect the viewpoint of men like Kipling, born or inhabiting India with the intrinsic belief that they were gods in all but name – ‘lesser gods’, if you will.

In Death of a Lesser God, James Whitby’s father, Charles, is an arch – and unrepentant – colonialist, chafing under the post-independence regime. Yet, he refuses to abandon India. In many ways, it is all he has known, and he is tied to it, much as Ahab eventually found himself lashed to the whale.

Death of a Lesser God by Vaseem Khan is published on 10 August, 2023. It‘s the fourth in his Malabar House series

Vaseem is the author of two award-winning crime series set in India, the Baby Ganesh Agency series in modern Mumbai, and the Malabar House historical crime novels in 1950s Bombay. His first book, The Unexpected Inheritance of Inspector Chopra, was selected by the Sunday Times as one of the 40 best crime novels published 2015–2020, and is translated into 17 languages. In 2021, Midnight at Malabar House won the Crime Writers Association Historical Dagger.

Born in England, Vaseem spent a decade working in India. In 2023, he was elected the first non-white chair of the 70-year-old UK Crime Writers Association.

For more on the historical background to Vaseem’s novels you may enjoy reading his earlier Historia feature examining Partition and the scandal that shocked India: Partition, politics, and a prime minister’s passion.

If you’re interested in the history of India, you may also like:

1920s Bangalore, a city of diversities by Harini Nagendra

It’s time to remember Ganga Singh: maharaja, reformer, statesman by Alec Marsh

Unforgettable legacies of the East India Company by Vayu Naidu

Re-examining the history of Empire in fact and fiction by Tom Williams

Finding empathy – the complexities of writing Robert Clive by Diana Preston

Images:

- Rudyard Kipling, photo by Elliott & Fry, colourised by Cassowary Colorizations: Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

- Writers’ Building, Calcutta, postcard, 1908: Paper Jewels via Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

- Rudyard Kipling by John Collier, 1891: Wikimedia (public domain)

- Maliks Ghat, Calcutta, photograph c1890s: US Library of Congress (public domain)

- US soldiers remove their shoes before entering the Calcutta Jain Temple, 1943: US National Archives via Wikimedia (public domain)

- Chowringhee Rd, Calcutta, postcard, 1905: Paper Jewels via Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)